History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.—James Joyce, Ulysses

It’s been a prevalent notion. Fallen sparks. Fragments of vessels broken at the Creation. And someday, somehow, before the end, a gathering back to home. A messenger from the Kingdom, arriving at the last moment. But I tell you there is no such message, no such home―only the millions of last moments…nothing more. Our history is an aggregate of last moments.―Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

by Sanjay Perera

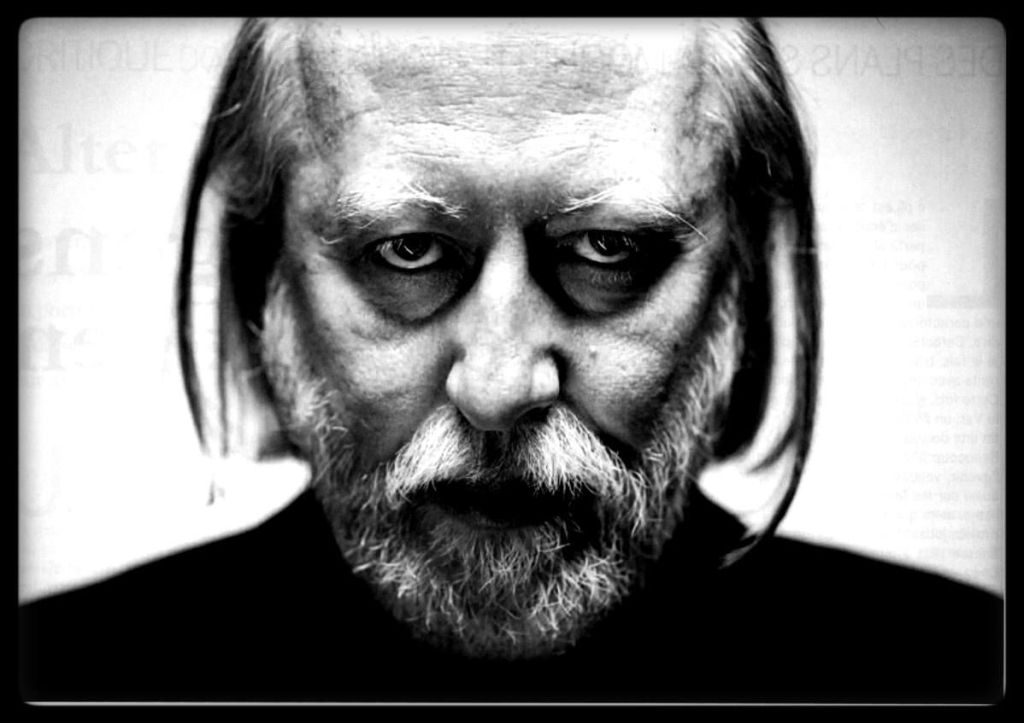

PERFECTIONIST, uncompromising stylistically, unyielding in his worldview. Hungarian writer and novelist László Krasznahorkai was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature last month. The writer whose prose pours across pages as incessant sinuous rills of sentences with barely any punctuation at times is perhaps the last genuine literary author left pushing narrative boundaries. With the exceptions of arguably Thomas Pynchon and certainly the late greats—W.G. (Max) Sebald and Thomas Bernhard—it is difficult to think of others in this time who are grappling sincerely with ideas as well as narrative art creating memorable work. The collapse of communism in Hungary is the epicentre of Krasznahorkai’s work; all that radiates from this seismic event is expressed in some form in much of his writing. Though he explores and is open to other civilisations, cultures and historical contexts in later work, the European literary influence and that of Dostoevsky, Melville, Kafka, Nietzsche, Pynchon, Sebald and others can be discerned.

Despite those eager to embrace and label him as a postmodernist, that misused and jaded term does not apply to Krasznahorkai who defies categorisation. Characteristics that are claimed to be ‘postmodernist’ are noticeable in even Sterne, Joyce or Melville but they are decidedly not ‘postmodern’—a term that has become notorious as it has lost its significance and meaning due to being applied to almost anything and everything post-mid-twentieth century (or any other century) that is seemingly experimental, against the norm, authority, hierarchy. Krasznahorkai is his own man and has a distinctive voice: his often dense and demanding work requires careful attention, actual patience, a love for the written word and language; the willingness to be dragged into apocalyptic visions, teeter at the edge of the abyss and even plunge into it: yet be shown occasional glimmers of light that shimmer through materiality and the veil of ignorance—it is not everyone’s idea of reading. Not that he is without humour when least expected. And there are moments, or scenes that describe the aftermath, of sudden violence. But if he is engaged on his own terms and given a chance for the labyrinthine flow of words to unwind in the consciousness: an unforgettable effect is created that can precipitate visionary and stunning insights.

Not only are his books available in apparently at least 40 languages generating a wider reach over the years, those in English have been awarded translation prizes for their brilliance: the prose and ideas come across clearly and effectively. Indeed, the humility in his work makes it unique and reflects his personality as it does come across in his interviews. In other words, he is devoid completely of the pretensions to invention, intellectuality, pseudo-profundity and so-called cleverness of those who are delighted to be called ‘postmodern’: Krasznahorkai will be remembered as perhaps a modern Melville who is given the recognition the latter was denied in his lifetime (though the analogy is imperfect). ‘Postmodernists’, however, may perhaps be regarded one day as representatives of a fad: this is a reference to those deemed writers or artists as opposed to thinkers and philosophers who unfortunately have been cast under the same rubric: those who should accurately be regarded as poststructuralist instead, e.g., Foucault and Derrida.

In the tense silence the continual buzzing of the horseflies was the only audible sound, that and the constant rain beating down in the distance, and, uniting the two, the ever more frequent scritch-scratch of the bent acacia trees outside, and the strange nightshift work of the bugs in the table legs and in various parts of the counter whose irregular pulse measured out the small parcels of time, apportioning the narrow space into which a word, a sentence or a movement might perfectly fit. The entire end-of-October night was beating with a single pulse, its own strange rhythm sounding through trees and rain and mud in a manner beyond words or vision: a vision present in the low light, in the slow passage of darkness, in the blurred shadows, in the working of tired muscles; in the silence, in its human subjects, in the undulating surface of the metaled road; in the hair moving to a different beat than do the dissolving fibers of the body; growth and decay on their divergent paths; all these thousands of echoing rhythms, this confusing clatter of night noises, all parts of an apparently common stream, that is the attempt to forget despair; though behind things other things appear as if by mischief, and once beyond the power of the eye they don’t hang together. So with the door left open as if forever, with the lock that will never open. There is a chasm, a crevice.

―László Krasznahorkai, Satantango

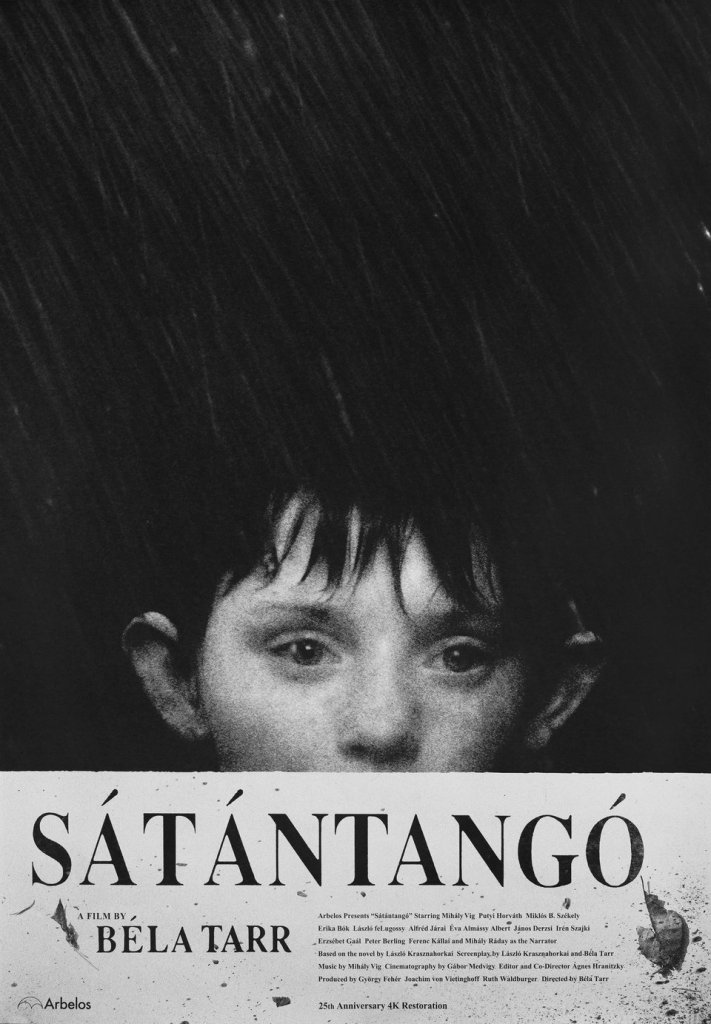

His first novel Satantango showcases his literary gifts. It is set at what appears to be the end of the Hungarian communist regime, as a conman returns to take hold of the money from a failing collectivist farm claiming to help them. The scammer plays the saviour but neither he nor his accomplice shy from the threat of terror to get their way; but they are also police informants and not independent operators, their threats but damp squibs of confidence-men lighted under the gullible. There are crucial subplots and other characters that heighten the sense of collapse reflected in the state of buildings, absent morality; a pervasive paranoia and indifference to suffering. A theme in the book and other works of Krasznahorkai is that of the deceiver in the form of con artists; this hearkens back to The Confidence-Man (1857) by Herman Melville. A novella of Krasznahorkai’s, Spadework for a Palace, is about a neurotic librarian called ‘herman melvill’ obssessed with the work of Melville, a man quite dysfunctional on many levels: aberrant psyches are embodied by many of his characters.

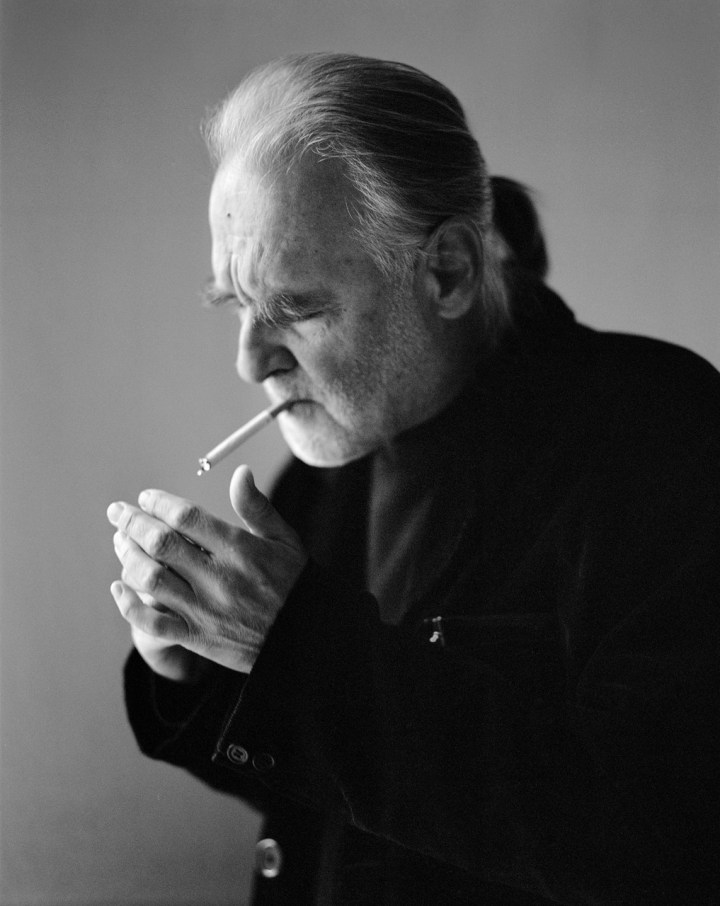

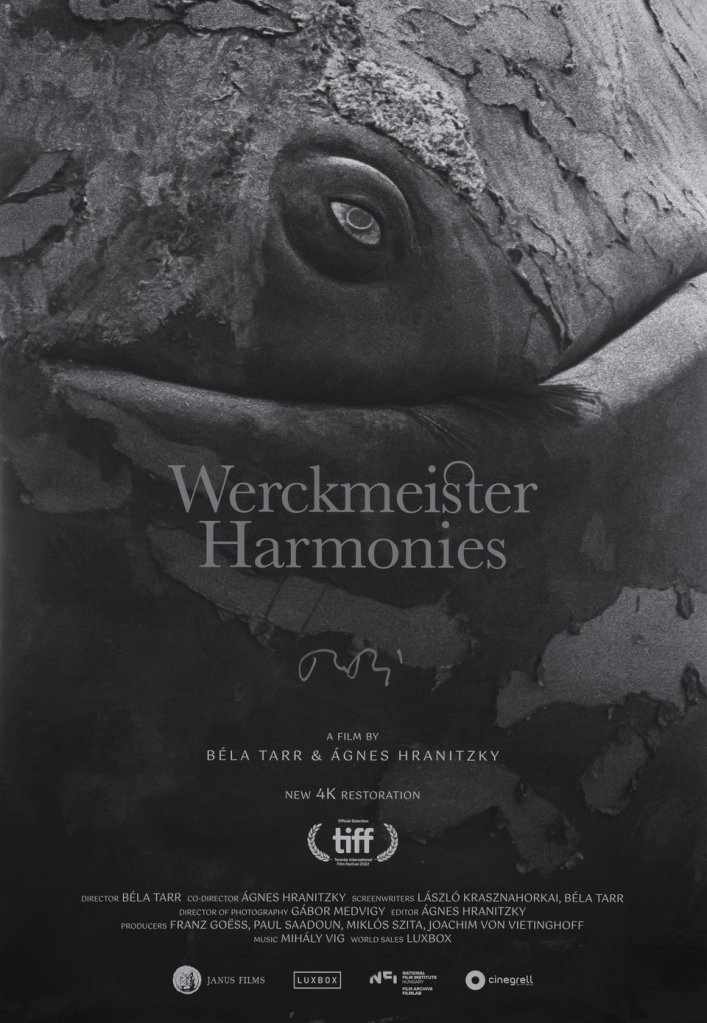

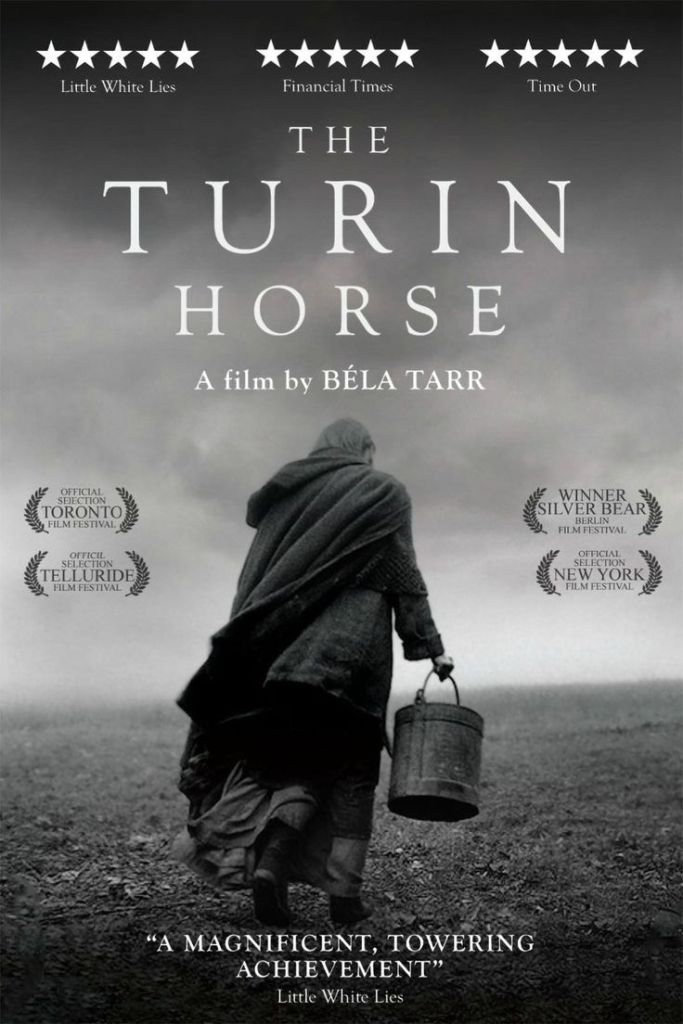

Satantango was made into an iconic seven hour film by Hungarian director Béla Tarr (who died on Jan 6 this year).[1] Tarr’s film is a slow burn that is as hypnotic as the unceasing flow of prose from Krasznahorkai (though some complain about its perceived longeurs); he is a master of the long take in films similar to the legendary filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky (though the analogy ends there; see “Megalopolis”). The stark, stunning and, at times, hauntingly lyrical black-and-white films featuring his collaboration with Krasznahorkai complements effectively—and brings brilliantly into relief visually—some of the latter’s ideas. Another of Tarr’s filmic collaboration is The Melancholy of Resistance, the novel that brought Kraznahorkai international recognition. However, the movie was called Werckmeister Harmonies which is the title of the main section of the book. It is set in a Hungary close to the end of the communist regime when a circus comes to Kossuth Square near Budapest in the dead of night carrying in a massive container, as its main exhibit, the carcass of the world’s largest whale .

Here we have to acknowledge the fact that there were ages more fortunate than ours, those of Pythagoras and Aristoxenes, when our forefathers were satisfied with the fact that their purely tuned instruments were played only in some tones, because they were not troubled by doubts, for they knew that heavenly harmonies were the province of the gods. Later, all this was not enough, unhinged arrogance wished to take possession of all the harmonies of the gods. And it was done in its own way, technicians were charged with the solution, a Praetorius, a Salinas, and finally an Andreas Werckmeister, who resolved the difficulty by dividing the octave of the harmony of the gods, the twelve half-tones, into twelve equal parts.—Béla Tarr

The shadowy presence behind the sinister enterprise is the so-called ‘prince’ who deploys demagoguery to instigate restless crowds that gather in the square to riot. The central character, a simpleton named Valuska, navigates his way through the upheaval, and ruthlessness of a neo-fascist attempt to take over the town by exploiting the uprising: but he is also fascinated by the dead whale whose eye he stares into. The black body of the whale, a contrast to Melville’s live great white whale Moby-Dick, is a complex symbol of many things including the corruption, moral decay, entropy of society or social order—the natural disorder of things as such—and loss of faith and spiritual collapse in particular (though Krasznahorkai is correct in not being keen to comment on such matters in public leaving interpretation to others). While Melville’s creature in its grandeur, inexplicability, power and destructive force is an intimidating wonder: the dead whale is akin to Nietzsche’s ‘death of God’ in which all that is awe-inspiring even when it may bring danger and death along with it—is negated by its antithesis; the lifeless, that which is despairing and gloomy.

(The dead whale is also a reminder of a renowned collection of essays by prominent intellectuals from 1949 entitled appropriately The God that Failed on their disillusionment with the realities of post-World War II communism: and the start of their opposition to it after supporting it initially.)

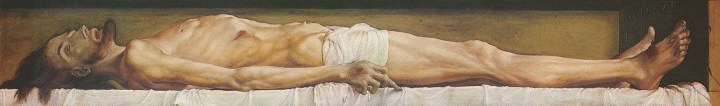

The simple and mild character of Valuska is reminiscent of Dostoevksy’s Prince Myshkin in The Idiot: the latter embodies Christian ideals, and tends to be idealistic and positive in nature but his simplicity and sincerity do not lead to a good outcome. Similarly, Valuska who is treated as the village idiot has a parallel fate to Myshkin. The reality of the ineluctable decay inherent in matter as diametrically opposed to the everlasting nature of spiritual liberation free of physical limitations underpins much of Krasznahorkai’s work but it is less obvious than in Doestovesky. Hence, in The Idiot a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger—“The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb” (1522)—is a central image in the book; in it the body of Christ in death undergoes putrefaction, which to Doestoevsky can challenge spiritual faith, as it depicts the victory of blind nature over a great Being: principally, that it forces questioning of the Resurrection; particularly, for common folk the sight of a decomposed body is sufficient for most to doubt an afterlife, at least one that posits eternal spiritual manumission from the undeniable reality of physical suffering. The whale in Krasznahorkai has an analogous effect; the inevitability that things fall apart, the centre cannot hold, death and decay an inescapable reality; all that exists in the world is subject to collapse.

He would see that birth and death were only two tremendous moments in an eternal waking, and his face would glow with amazement as he understood this; he would feel—gently he grasped the copper handle of the door—the warmth of the mountains, woods, rivers and valleys, would discover the hidden depths of human existence, would finally understand that the unbreakable ties that bound him to the world were not imprisoning chains and condemnation but a kind of clinging to an indestructible sense that he had a home; and he would discover the enormous joys of mutuality which embraced and animated everything: rain, wind, sun and snow, the flight of a bird, the taste of fruit, the scent of grass; and he would suspect that his anxieties and bitterness were merely cumbersome ballast required by the live roots of his past and the rising airship of his certain future, and, then—he started opening the door—he would finally know that our every moment is passed in a procession across dawns and day’s-ends of the orbiting earth, across successive waves of winter and summer, threading the planets and the stars. Suitcase in hand, he stepped into the room and stood there blinking in the half-light.

―László Krasznahorkai, The Melancholy of Resistance (upon which Werckmeister Harmonies is based.)

The idea of the dead whale figures in another of his tales, “Universal Theseus” in the collection of stories published much later entitled The World Goes On; it gives an ironic take on those who insist on ‘a clear meaning’ in literary works. This is presented as part of a series of lectures by the narrator in the piece, as Krasznahorkai provides a self-deprecatory dig at his own work:

[T]he allegedly largest whale in the world, had already caused plenty of mischief along the way before arriving here.

So these local citizens knew quite a lot, and if I said they suffered torments of anxiety on account of this, no one would wonder, for, after all, the inhabitants of this town lived in a world where everyone, in a rising tide of hatred caused by their fear of human nature, was convinced that humanity would destroy itself. So that they were aware of a great many things, trivial details as well as essentials—namely, what lay hidden behind that wall of corrugated tin, they agreed that behind it lay a dreadful, enormous whale—but that this whale might be concealing something, that in fact the whale itself might be a substitute for something else, in other words this enormous carcass was simultaneously both messenger and message . . . well . . . the townspeople were entirely unaware of this…

Unable to find any ultimate meaning we feel crushed enough already to be fed up with a literature that pretends there is such a thing and keeps hinting at some ultimate meaning. We refuse to put up with a literature that is essentially, in its very fiber, so radically mendacious, we are in such dire need of an ultimate meaning that quite simply we can no longer tolerate the lies, we can no longer put up with this literature, and in fact it is not outrage, but boredom and the squalid level of those lies that make us gag; well then, given the above, in fullest possible agreement with you gentlemen, I myself can now announce that to claim there is a book that knows [reference to The Melancholy of Resistance], that promises to reveal and narrate to us and only us all that breaks loose in the wake of one of these gigantic whales, is either an insidious effrontery or the vilest drivel, in a word, lies, of course, for nobody knows what really is unleashed at these times, no one, and no book knows that, because that certain something lies completely covered up by the whale.

Placing the humour aside, with some imagination this passage could describe the approach many adopt towards religion in the quest for significance to the world, in religious texts, and our lives; the desire for meaning, its elusiveness and the struggle to rationalise existence even when we cannot explain the human dilemma convincingly, is part of the melancholy in Krasznahorkai’s work; its pessimism, its bleak vision. Furthermore, Krasznahorkai does not seem to want to clarify his stance in many instances despite what it seems to suggest: the ambiguity is deliberate. He leaves us looking through a glass, darkly. And in the case of the person giving the lecture in “Universal Theseus” it appears he may well be a patient in a sanatorium which is in reference to Doestoevsky’s Myshkin and Melancholy’s Valuska. But an insight into the world does seem to be an ability given to ‘holy fools’ or analogues of them: an idea found in the Eastern Orthodox Church. This connects to another character of Dostoevky’s who is far from being a fool, and it involves the notion of decay in a crucial scene (that correspondingly segues with Krasznahorkai’s world).

In Dostoevsky’s masterwork, The Brothers Karamazov, the key figure Alyosha undergoes a spiritual crisis when confronted with the corpse of his beloved mentor Father Zosima of the Russian Orthodox Church. Contrary to what was expected traditionally from the remains of the saintly, there is the odour of corruption coming from his body: this confuses Alyosha who endures a loss of faith as he leaves the monastery to confront the world. This is yet another link originating from the “Body of the Dead Christ” in The Idiot, straight through Karamazov and then to the carcass of the whale in Krasznahorkai. As Alyosha eventually understands, the corruption of the material world is illusory, it only hides what lies behind it, what shines around but obscured by human ignorance and the darkness emanating from the evil this engenders. (Dostoevsky like his compatriot many years later, Tarkovsky, was openly a man of faith: Krasznahorkai demurs on such matters in his work, but it is there.)

The apparent ascendancy of darkness is taken to extremity, without the offer of hope, in Krasznahorkai’s final collaboration with Tarr. Tremendous and unnerving The Turin Horse centers on the horse whipped by its owner for not moving on January 3rd 1889 in Turin; philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche who in actuality was in the vicinity apparently threw his arms around the horse’s neck, and collapsed (not shown in the film): he had a mental breakdown—although he recovered temporarily—was lost in his own world, ultimately degenerating into a vegetative state till his death a decade from his collapse. The question Krasznahorkai asked when developing the story which eventually turned into the screenplay for Tarr’s film: what happened to the horse afterwards? The film explores its return with the owner in a fictional account that reveals their hard life on a farm. The apocalyptic finale where light is erased by darkness echoes the end of Satantago: the doctor who writes what he observes in his collective finally boards up his room and seals himself in darkness, as a madman rings the bell of a ruined church shouting the ‘Turks are coming’—The Turin Horse goes further than that justifying Tarr’s decision to make it his last feature film. In its own way it is in resonance with Arthur C. Clarke’s “The nine billion names of God”.

In Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming a naive off-kilter Hungarian aristocrat appears after years of absence, and is another Myshkin-like character. Unlike the others he is of a romantic bent but in a most disturbing manner that leads to disastrous consequences for him. The book is also a devastating commentary on the vicious mendacity of mass media, politicos, and the fickleness of public sentiment. There is an important subplot involving an eccentric Professor on the run from neo-Nazi biker thugs which provides the overt action that underscores the violence of the book (which appears in subtler forms). There is also a dread that fills the pages resulting in a finale which for some may be associated with horror novels, and arguably Krasznahorkai at his bleakest; it was initially regarded as his last novel.

The darkness does not lift but becomes yet heavier as I think how little we can hold in mind, how everything is constantly lapsing into oblivion with every extinguished life, how the world is, as it were, draining itself, in that the history of countless places and objects which themselves have no power or memory is never heard, never described or passed on.—Sebald, Austerlitz

Time, said Austerlitz in the observation room in Greenwich, was by far the most artificial of all our inventions, and in being bound to the planet turning on its own axis was no less arbitrary than would be, say, a calculation based on the growth of trees or the duration required for a piece of limestone to disintegrate, quite apart from the fact that the solar day which we take as our guideline does not provide any precise measurement, so that in order to reckon time we have to devise an imaginary, average sun which has an invariable speed of movement and does not incline towards the equator in its orbit.― W.G. (Max) Sebald (1944-2001), Austerlitz

History is a nightmare that Krasznahorkai is trying to awaken from, and he believes so are the rest of us. The human condition is unmitigatedly shaped by the past of our countries, society, our choices within these contexts. In our time, it is manifest that we cannot escape world historical forces; living in a society that values freedom or does not; one which imposes barbaric beliefs, ideologies celebrating violence masquerading as religion; states and international organisations that attempt to control all human activity; constraints on economic activity; the attempt to practice genuine non-violent spirituality: all are funneled into a vortex of darkness with an outcome spread across the planet. Present post-communist Europe is the obverse of past Europe under communism: people are still afflicted by the same malady of spiritual emptiness, hardship, conflict, dishonesty, greed, betrayal by ‘leaders’ and power structures. And a survey of the West today reveals what could be an irreversible decline of Western civilisation that would confirm much of Krasznahorkai’s views.

His latest work translated into English is Herscht 07769. The chief character Florian Herscht is not only a gentle giant but yet another variation of Dostoevsky’s Myshkin. Krasznahorkai pursued legal studies briefly but abandoned it for writing; and, he does have profound knowledge of music, as shown in his use of variations on themes, leitmotifs, cadenzas among much else that shapes his form of writing: repetition is a function of his literary expression and ideational development.[2] Florian has great physical strength and is a robust contrast to Valuska; he is obsessed with an idea from particle physics which be believes implies the end of the universe, absolute nihilism: and he is on a mission to warn German Chancellor Angela Merkel about this. He lives in former communist Thuringia which is part of current Germany and the birthplace of Bach, Goethe, and Schiller; meanwhile, statues of Bach are being desecrated, Florian gets entangled with neo-Nazis, and escaped wolves are said to roam the area causing public alarm (at times the book seems a European version of a Pynchon novel).

His view was that they had lost the battle, and not only that, he added, but maybe even the war as well, because they were coming up from the sewers—as always occurred in these historical pauses, they emerged, ruining everything, destroying and debasing whatever they touched, degrading everything that was valuable, fouling what was sacred for others, spreading a disease against which there was no vaccine, because it was not the pandemic that was the danger, but instead this infection, the main symptom of which was that people showed the worst side of themselves, and they were weak, immeasurably weak and immeasurably idiotic, and what can we do about this.―László Krasznahorkai, Herscht 07769

The book then escalates into a chase reminiscent of a thriller with unexpected extreme violence; this culminates inevitably in a dark end—but with what appears as empathy between a hunted man and runaway wolves with Bach’s “Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden” (“Forgive, Most High, my sins”) issuing from a church: an unusual ‘positive’ turn in Krasznahorkai’s work. Yet, the redemption hoped for arising from the euphonious cantata seems to be denied to those undergoing suffering though the music attests otherwise; it is a salvation that many strive for collectively though it is elusive: but it is there, and Krasznahorkai does not negate that. If Tarr’s black-and-white films provide the visual yin of Krasznahorkai’s work: the meditative, poetic, powerful films of Tarkovsky are the filmic yang—Bach’s music flowing through them—with most films full of various colours from changing film stock: unashamedly spiritual, reflecting his artistry and struggle against the Soviet regime. The wilful post-communist director of resignation and resistance; the filmmaker under communist repression shining through his faith and resilience.

Notwithstanding, positivity is not as surprising as some may think in Krasznahorkai’s oeuvre as this excerpt from his Nobel Prize banquet speech, 10 December 2025, reveals:

I give my thanks to Franz Kafka, whose novel Das Schloss [The Castle] I read when I was twelve years old so that I would be accepted in the circle of my brother, six years older than me; and so my fate was sealed,

…To Ernő Szabó and Imre Simonyi, unknown poets of Gyula, whom I have always admired, and who bore my admiration in a manner worthy of a man,

To Péter Hajnóczy, the most staggering among Hungarian short story writers, who succumbed in his struggle with his phantasms, and thus is no longer among the ranks of the living,

I give my thanks to the artists of Classical Greece,

To the Italian Renaissance,

To Attila József, the Hungarian poet who showed the magical power of words,

To Fyodor Mihailovitch Dostoyevsky,

To my older brother, who often carried me home from kindergarten, because of which I became infinitely grateful to him, as he showed me that there could be another way of looking at the world, not just that which is given,

To William Faulkner,

To the city of Kyoto,

To Thomas Pynchon, beloved friend, to whom I owe deep gratitude,

To Johann Sebastian Bach, for the Divine,

To Patti Smith, for she is the eternal warning: never submit to anyone,

To the voices of Agnes Baltsa, Natalie Dessay, Jennifer Larmore, Monserrat Caballe, Teresa Berganza and Emma Kirkby,

To Béla Tarr, who created colours by making them disappear, because in his great films he tried to speak as the sinner who nevertheless, with all his sins, must still be loved,

To Allen Ginsberg, the friend who is no longer among the ranks of the living, because the time of his death had come,

To the literati of Imperial China,

To Max Sebald, the marvellous writer and friend who is no longer among the ranks of the living, as he gazed for too long at one single blade of grass in the meadow,

To the last wolf in Extremadura,

To nature, that was created,

To Prince Siddhartha,

To the Hungarian language,

To God.

I would set you free, if I knew how. But it isn’t free out here. All the animals, the plants, the minerals, even other kinds of men, are being broken and reassembled every day, to preserve an elite few, who are the loudest to theorize on freedom, but the least free of all. I can’t even give you hope that it will be different someday—that They’ll come out, and forget death, and lose Their technology’s elaborate terror, and stop using every other form of life without mercy to keep what haunts men down to a tolerable level—and be like you instead, simply here, simply alive. . . ―Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

Still, the epigraph of Herscht 07769 is “Hope is a mistake”. And so it is easy to mistake Krasznahorkai’s books as irredeemably nihilistic, that hope is pointless. But that is not quite what the Krasznahorkaian project implies. The dark cosmic atmosphere of much of his work is a presentation of the world as we live it even if we try to see it differently, in a hopeful manner; a journey through dark matter and energy but reaching an event horizon paradoxically eventuating an explosion of light and energy—the rejuvenation of cosmic forces. There is a parallel here to the Nietzschean eternal recurrence, striving to give meaning to life via artistic expression but with Krasznahorkai’s added dimension of trying to find at times compassion or empathy. An accurate way to describe Krasznahorkai’s ideas is that they are, perhaps, Schopenhauerian. And Schopenhauer was a decisive influence upon Nietzsche. The great melancholic pessimism of Krasznahorkai’s work: the futility of our existence through the way we live; compassion for animals (which for Schopenhauer was part of compassion itself as the basis of morality); that music is of universal importance (to Schopenhauer it is a fundamental metaphysical principle of reality)—are not only consonant with Schopenhauer who in turn was influenced by Vedantic and Buddhist philosophy: but concordantly, Krasznahorkai too is impacted by Eastern philosophy such as Buddhism and Taoism (and, of course, Christianity). Some of his work that explores such connections to the East include Seiobo There Below and A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East.

Despite the darkness, despair, disillusionment from hope, a world wherein hardly any good deed goes unpunished—undergirded by the eschatology of the end of the universe: Krasznahorkai understands there is a balance and resilience that still keeps all things connected, the cosmos still operating; irrespective of the discordance of life, the chaos of the world, the Werckmeister tuning system that artificially imposes a certain order or control that can lead to disharmony: as opposed to the natural harmony that mysteriously holds everything together: the Pythagorean music of the spheres that is Divine and inaudible to us; humanity carrying on: as many continue looking for answers through activity, art, and a sense of morality. Again, in a cycle of paradox, this cannot negate the reality of impermanence, unreliability, brittleness of the world, hopelessness of positive sentiments, transitoriness of happiness; the fullness of suffering that defines life; all underwritten by the contingent nature of matter: a prime example being the decomposition of the body as shown in an extract from the final lines of The Melancholy of Resistance:

Everything was there, it is simply that there was no clerk capable of making an inventory of all the constituents; but the realm that existed once—once and once only—had disappeared for ever, ground into infinitesimal pieces by the endless momentum of chaos within which crystals of order survived, the chaos that consisted of an indifferent and unstoppable traffic between things. It ground the empire into carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and sulphur, it took its delicate fibres and unstitched them till they were dispersed and had ceased to exist, because they had been consumed by the force of some incomprehensibly distant edict, which must also consume this book, here, now, at the full stop, after the last word.

However, this reflects particular forms of Buddhist meditation on the ephemerality of all phenomena: mental, emotional and physical. The meditation known as ‘Insight meditation’ concerns the concept of ‘dependent origination’ where everything, the phenomenal world, is causally linked; all arises and falls into decay through a concatenation of events, connections, or processes, like the continuous words in the winding sentences of Krasznahorkai [see end note2]. This underpins the doctrinal crux of Buddhism, the Four Noble Truths: suffering; the cause of suffering; the end of suffering; the path leading to the end of suffering. Krasznahorkai takes us to suffering and the cause of suffering, and leaves us there; we have to find our own way; not that he is callous but he does not have the ultimate answer, or at least that is the impression his writing leaves us with; he shows us things as he understands or sees them, and leaves us to make our own judgement; he has no choice in this as we are confronted by our existence as an aporia, a perplexity and challenge, a burden that is unsurpassable. We stand before an infinite abyss that apparently cannot be transcended; some fall into it. But in truth it is a maximal expression of the darkness we face; yet through so much around us, those who bother to strive in trying to create a meaningful existence, the beauty of artistic expression such as the music of Bach: we grasp that the darkness is a veil across the temple that should be rent, it obscures the hidden light.

I would leave everything here: the valleys, the hills, the paths, and the jaybirds from the gardens, I would leave here the petcocks and the padres, heaven and earth, spring and fall, I would leave here the exit routes, the evenings in the kitchen, the last amorous gaze, and all of the city-bound directions that make you shudder, I would leave here the thick twilight falling upon the land, gravity, hope, enchantment, and tranquillity, I would leave here those beloved and those close to me, everything that touched me, everything that shocked me, fascinated and uplifted me, I would leave here the noble, the benevolent, the pleasant, and the demonically beautiful, I would leave here the budding sprout, every birth and existence, I would leave here incantation, enigma, distances, inexhaustibility, and the intoxication of eternity; for here I would leave this earth and these stars, because I would take nothing with me from here, because I’ve looked into what’s coming, and I don’t need anything from here.—László Krasznahorkai, The World Goes On

But like Kafka’s hapless protagonist in “Before the Law” we are waiting to pass through the door, to tear asunder that veil—that could reveal the way to emancipation, even salvation. The excerpt from Satantago above ends with these lines: “So with the door left open as if forever, with the lock that will never open. There is a chasm, a crevice.” It is a corollary of Kafka’s story. We wait all our lives trying to get past the gatekeepers or barriers preventing us from entering the portal that leads to liberation but are overwhelmed by the odds, obstructions, naysayers, prevaricators, the confidence-men, fear, lack of faith to cast aside mind-forged manacles—to walk into what we have always imagined, prayed for: finally to realise, if fortunate, that the path created for us is unique as are the challenges, they are for us alone to overcome. And so it is for the man in Kafka’s tale before that doorkeeper. At the end he learns that the door was meant only for him and no one else; and when it is too late witnesses “amidst the darkness a radiance which bursts out inextinguishably from the door of the law”. This seemingly desolate situation can, however, be redeemed through understanding that the abyss we think we are often falling into can be transformed; the nothingness is a void that can be filled; and the emptiness is a ‘God-shaped’ space that can be transmuted into light as we disregard the gatekeepers and walk through the door that is always open for us.

What is it then that this desire and this inability proclaim to us, but that there was once in man a true happiness of which there now remain to him only the mark and empty trace, which he in vain tries to fill from all his surroundings, seeking from things absent the help he does not obtain in things present? But these are all inadequate, because the infinite abyss can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object, that is to say, only by God Himself.

He only is our true good, and since we have forsaken Him, it is a strange thing that there is nothing in nature which has not been serviceable in taking His place; the stars, the heavens, earth, the elements, plants, cabbages, leeks, animals, insects, calves, serpents, fever, pestilence, war, famine, vices, adultery, incest. And since man has lost the true good, everything can appear equally good to him, even his own destruction, though so opposed to God, to reason, and to the whole course of nature.—Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), Pensées VII(425)

End notes:

[1] Upon Béla Tarr’s passing from a series of illnesses, Krasznahorkai issued a statement that Tarr:

…was one of the greatest artists of our time. Unstoppable, brutal, unbreakable. When art loses such a radical creator, for a while it seems that everything will be terribly boring…Who will be the next rebel here? Who will come forward? Who will kick everything apart?

[2] Krasznahorkai’s observations in this interview reflect certain contemplation techniques and meditational practices in Buddhism:

Yes, because that is the other side of my books, which is very important for me and hopefully for my readers as well, mainly, repetition. Of course, this is one of the questions of sentences, of language. Repetition. This is a part of language that I use because Hungarian is a very musical language, but there is also here a very important issue: What does it mean to repeat something? When I was first in East Asia, in China and in Japan—and I went back again and again, actually for more than ten years I went back again and again—the only one thing that I could somehow understand, rather, guess at, was eternity. This is not an abstract idea, but this is an everyday reality. Many times I watched workers who built sacred places, monasteries, churches, in the Buddhist areas in Japan and it became more and more important to me to see how they work, namely, why is it so terribly important that a wood, a piece of wood, be so smooth, so absolutely without mistakes, I watched the workers and I didn’t understand because I thought that this was already perfect, but this was not perfect enough for him, I tried to see, I tried to understand why it was so important to make the same movement until I understood, or guessed, that it was absolutely not important what happened with the wood, the only thing that was important was the repetition of the movement, and this perfection of the piece of wood was only a consequence of this repetition, of this movement. Actually, I tried to understand, and perhaps I could understand eternity in a very simple way, namely, by watching somebody, the workers, the woman, somewhere, who made the same movements, absolutely the same movements, and I began to watch, for example, a faucet, how the water from the tap moves, how one drop of water leaves the edge of the tap, and this eternal movement led me to waterfalls. For example, in Schaffhausen, surprisingly, there is a wonderful waterfall. This is a waterfall where you can come very close to the water, very close, one meter or less, to try to follow the way of one drop.

[Featured picture credit: Pixabay. Top picture credit: Pinterest.]

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change, philosophersforchange.org. Thanks for your support.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International.