In 2011, the Arab Uprisings, the Libyan revolution, the UK Riots, the Occupy movements may make it as memorable a year in the history of social upheaval as 1968 and perhaps one as significant. Henceforth, demonstrators could be assembled in flash mobs that could occupy any site at a moment’s notice and submit corrupt businessmen, politicians, and others to the wrath of the people.

Political Insurrection as Media Spectacle

“In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation,” Guy Debord

In the past decades, media spectacle has become a dominant form in which news and information, politics, war, entertainment, sports, and scandals are presented to the public and circulated through the matrix of old and new media and technologies. By “media spectacles” I am referring to media constructs that present events which disrupt ordinary and habitual flows of information, and which become popular stories which capture the attention of the media and the public, and circulate through broadcasting networks, the Internet, social networking, cell phones, and other new media and communication technologies. In a global networked society, media spectacles proliferate instantaneously, become virtual and viral, and in some cases become tools of socio-political transformation, while other media spectacles become mere moments of media hype and tabloidized sensationalism.

Dramatic news and events are presented as media spectacles and dominate certain news cycles. Stories like the 9/11 terror attacks, Hurricane Katrina, Barack Obama and the 2008 U.S. presidential election were produced and multiplied as media spectacles which were central events of their era. In 2011, the Arab Uprisings, the Libyan revolution, the UK Riots, the Occupy movements and the other major media spectacles cascaded through broadcasting, print, and digital media, seizing people’s attention and emotions, and generating complex and multiple effects that may make 2011 as memorable a year in the history of social upheaval as 1968 and perhaps one as significant.

In retrospect, 2011 appears as a year of Popular Uprisings in an era of cascading media spectacle. Following the North African Arab Uprisings, intense political struggles erupted across the Mediterranean in Greece, Italy, and Spain, all of which faced economic crisis and cutbacks of social programs. In February and March 2011, workers and students in Madison, Wisconsin occupied the state capital building to protest and fight against cutbacks of their rights and livelihood when a rightwing Governor Scott Walker signed a bill to curtail union rights and cut back on social programs, including student aid and healthcare; Egyptians declared their solidarity with protestors in Madison and sent them pizzas. For weeks during the summer of 2011, there were also widespread demonstrations in Israel in which demonstrators, like in Tahrir Square in Cairo, occupied and set up a tent city in Tel Aviv to protest against declining living conditions and government policies in Israel.

In the face of the failures of neoliberalism and a global crisis of capitalism, tremendous economic deficits and debts in these countries, enabled and produced by unregulated neoliberal capitalism, there were calls by established political regimes to solve debt crises on the backs of working people by cutting back on government spending and social programs that help people rather than corporations. These struggles emerged globally with powerful protest movements against government austerity programs emerging in Spain, Italy, the UK, Greece, and other European countries, intensifying as capitalist economic crises intensified. In many of these struggles, youth played an important role, as young people throughout the world were facing diminishing job possibilities and an uncertain future in an era of global economic crisis.

From Occupy Wall Street to Occupy Everywhere!

In September 2011, a movement “Occupy Wall Street” emerged in New York as a variety of people began protesting the economic system in the United States, corruption on Wall Street, and a diverse range of other issues. The project of “Occupy Wall Street” was proposed by Adbusters magazine on July 13, 2011 and on August 9 Occupy Wall Street supporters in New York held a meeting for “We, the 99%.” On September 8 a “We are the 99 Percent Tumblr” was launched and on September 17 Occupy Wall Street protesters began camping out and demonstrating at Zuccoti Park in downtown New York close to Wall Street, setting up a tent city, that would be the epicenter of the Occupy movement for some months. Using social media, more and more people joined the demonstrations which received wide-spread media attention when police attacked peaceful demonstrators, yielding pictures of young women being pepper-gas sprayed by police. Mainstream media attention and mobilizing through social media brought more people to demonstrate and by the first weekend in October, there was a massive protest in lower Manhattan that marched across the Brooklyn Bridge and blocked traffic, leading to over 700 arrests.

The idea caught on and during the weekend of October 1-2, similar “Occupy” demonstrations broke out in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, Denver, Washington and several other cities. On October 5 in New York, major unions joined the protest and thousands marched from Foley Square to the Occupy Wall Street encampment in Zuccotti Park. Celebrities, students and professors, and ordinary citizens joined the protest in support, and daily coverage of the movement was appearing in U.S. and global media.

As it has come to own all major political stories of 2011, the Guardian was initially the place to go for Occupy Wall Street in the global media, with a Live Blog documenting news and actions related to the movement, and a web-page collecting their key stories with links to other stories at http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/occupy-wall-street (accessed on October 3, 2011). As the Occupy movement came to London, the Guardian focused special attention on their local occupation that involved dramatic clashes with the City of London and Catholic Church when occupiers set up a camp outside the venerable St. Paul’s Cathedral; church debates over how to deal with the occupation led high-ranking officials to resign.

In the U.S., police violence against the movement appeared to intensify its support and Al-Jazeera had telling footage on October 5 of demonstrators videotaping police beating up their colleagues, calling attention to the fact that the participants were using media to organize, to document violence against them, and to circulate their message globally, and that the Occupy Wall Street was traversing the globe as a major media spectacle of the moment.

During the weekend of October 8 and 9, large crowds gathered in Occupy sites throughout the country, and it appeared that a new protest movement had emerged in the United States that articulated with the global struggles of 2011. Like the movements in the Arab Uprising, the Occupy movements were using new media and social networking to both organize their movement and specific actions, as well as to document police and government assaults on the movement — documentation used to recruit more members and to intensify the commitment and resolve of its participants.

Occupy Wall Street was focused against financial capitalism and the corruption of the political class in the U.S., just as the 1990s anti-corporate global capitalism movement focused on the WTO, World Bank, IMF, and other instruments of global capital. In Greece, Spain, and Italy, people were demonstrating against these same institutions of global capitalism, as well as their own national governments. Like the Arab Uprisings, the Occupy Wall Street and other anti-corporate movements were outside of the domain of old-fashioned party politics, embraced diversity and tended to be leaderless. Although after meeting with Egyptian and other militants, some members of Occupy Wall Street indicated that they were going to search for specific issues that could lead to particular actions, so far no specific demands have been made to define the movement as a whole, although specific actions are being undertaken by some Occupy groups.

Interestingly, many of the tactics and goals of the Occupy movement replicated the politics and vision of Guy Debord and the Situationalist International,[1] creating situations, demonstrating outside of organized party or movement structures, using slogans and art of different forms to raise consciousness and inspire revolutionary movements. The year 2011 was looking more and more like 1968 with eruptions of struggle, police and Establishment brutality, and renewed protest and actions. Yet new media and social networking were creating new terrains of struggle. In using new media and social networking, the Occupy movements had the same decentralized structure as the computer networks they were using, and the movement as a whole had a virtual dimension as well as people organized in specific spaces. Hence, even if people were not occupying the spaces where the organizing and living were taking place they could participate virtually and be mobilized to participate in specific actions.

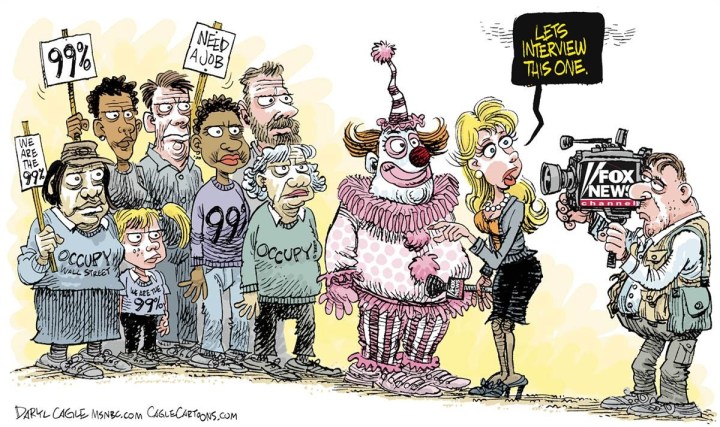

While the rightwing Tea Party movement which had helped the Republicans win Congress in 2010 and block all and any progressive and even mildly ameliorative initiatives, were hierarchical and top-down, the Occupy movements were genuinely bottom-up. The Occupy movement exemplified Deweyean strong democracy, was highly participatory, and experimental in its ideas, tactics, and strategies. While the Tea Party was financed by rich rightwing Republicans like the Koch brothers and had a national television network in Fox News to promote their goals and fortify their troops, the Occupy movements produced their own media including their own website, news media, videos, and Livestream that broadcast live action taking place in Occupy sites (see the Occupy Wall Street website at http://occupywallst.org/ [accessed on January 3, 2012] and Livestream at http://www.livestream.com/occupywallstnyc [accessed on January 3, 2012]).

As Michael Greenberg points out, by the middle of October, polls indicated that more than half of Americans polled had a positive view of the movement:

By mid-October, according to a Brookings Institution survey, 54 percent of Americans held a favorable view of the protest. Suddenly, or so it seemed, there was less talk of budget cuts that would limit, if not dismantle, social insurance programs such as Medicare while extending Bush’s tax cuts, and more talk about how to deal with economic inequality.

Several events pointed to an altered political climate. In New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo partially reversed his opposition to extending the so-called millionaire’s tax, pushing through legislation for a higher tax rate for the wealthiest New Yorkers. Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan Chase abandoned plans to charge a monthly fee to use their debit cards after an outpouring of indignation from customers—a minor event in the larger picture, but indicative of the public’s rapidly shifting mood.

More significantly, in Ohio 61 percent of voters rejected a referendum favored by Republican Governor John Kasich that would have severely restricted the collective bargaining rights of 360,000 public employees. And in Osawatomie, Kansas, on December 6, President Obama gave a speech that echoed almost verbatim what I had been hearing from protesters in Zuccotti Park. Obama deplored “the breathtaking greed of a few” and called the aim to “restore fairness” the “defining issue of our time.”[2]

The Occupy movements had generated a new political discourse that focused on economic inequalities, greed and the corruption of Wall Street and financial institutions, and the need for people to organize and demonstrate to force the government to meet their needs. As evidence that the Occupy movements were constituting a threat to the established system of power in November 2011, police and city governments closed down some of the biggest Occupy tent sites, sometimes violently, yet people continued to rally to the cause of the movement and demonstrations, occupations, and actions continued through the year. The brutality pictured in the closing down of the Occupy Wall Street site on December in Z park presented images of a fascist police state as images documented police beating up demonstrators, tearing apart and bull-dozing their camp-sites, and throwing their possessions in garbage trucks, including the Occupy Wall Street library that had collected over 5,000 books.

One of the main features of the Occupy movements was having media on hand to document their activities and those of police brutality and the spectacle of police throughout the United States brutally tearing down Occupy camps made the U.S. look like the thug regimes overthrown in the Arab Uprisings. The documentation accumulated of brutal police power provided material to radicalize new members and harden the resolve of the experienced ones that made possible a continuation of radical Occupy movements in the future.

After the political establishment shut down some of the major Occupy sites, like Occupy Wall Street, members began taking specific actions, transforming public spaces into “temporary autonomous zones” occupied temporarily by flash mobs of protestors. As Michael Greenberg indicates:

On December 1, for instance, protesters gathered in front of Lincoln Center to await the end of the final performance of Philip Glass’s opera Satyagraha, about the life of Gandhi. The idea was to dramatize their affinity with Gandhi’s method of nonviolent resistance. The following day, occupiers launched twenty-four hours of dance, “radical theater,” and “creative resistance” near Times Square meant “to educate tourists and theater-goers about OWS” and to demonstrate “a more colorful image of what our streets could look like.” December 6 was the day to “reclaim” selected bank-owned vacant homes in poor neighborhoods, reinstalling a handful of willing families that had been foreclosed upon and evicted. On December 12 there was a march on Goldman Sachs’s offices in Manhattan. On December 16 there was a rally at Fort Meade in Maryland where Private Bradley Manning, a hero to the movement, was standing trial for allegedly releasing classified government documents to WikiLeaks. The next day, more rallies were scheduled in New York and elsewhere, this time for immigrants’ rights. And so on.[3]

On December 16, the third month anniversary of the Occupy Wall Street movement happened to correspond to the first anniversary of the death of the vegetable vendor Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia who had set himself on fire and burned to death in protest, a media spectacle that was frequently taken as the spark that ignited the Arab Uprisings. As I argued above, the Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Everywhere! Movements were inspired by the Arab Spring, creating an American Autumn and Winter that guaranteed that 2011 would long be remembered in history books and popular memory as a time in which media spectacle took the forms of political resistance and insurrection.

As 2012 began to unfold, Occupy movements continued to undertake actions throughout the U.S. and the globe. In the U.S. and other countries, the movement had morphed from being primarily located in tent cities and occupations of specific sites to groups focused on particular actions. The Movement’s base was expanding to include individuals who had not participated in the first wave of occupations and to make coalitions with varying groups for targeted actions.

The Occupy groups and their allies could point to specific victories in early 2012, to which their movements had partially contributed. On January 18, 2012, major Internet industry web-sites went black in a day of protest against a proposed Congressional bill Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and a Protect Identity Property Act, which opponents claim could lead to online censorship and force some websites out of business. By midday, Google officials asserted that 4.5 million people had signed its petition against SOPA,[4] while Wikipedia claimed that 5.5 million people had accessed the site and clinked on a link that would put them in touch with local legislators to register their opposition to the act. Evidently, the action had an impact as politicians who had been for the bill, suddenly indicated opposition to it, and the bill’s sponsors withdrew it for further consideration.

On January 18, 2012, the Obama administration announced it would temporarily deny a permit for the building of the highly toxic Keystone XL Pipeline which would have transported extremely dirty oil from a vast oil deposit in Alberta, Canada, to refineries on the Texas Gulf Coast.[5] And on the same day, activists were celebrating in Wisconsin having received over one million signatories to have a recall election to potentially unseat Governor Scott Walker who was financed with ultra-right wing Tea Party movement money and had attacked union bargaining rights in a highly publicized affair that led union workers, students, activists and their supporters to occupy the Madison Wisconsin state capital in protest in May 2011,[6] linking Occupy movements in the Middle East with the U.S. and anticipating the Occupy Wall Street movement by some months.

Hence, new politics and subjectivities were emerging from specific sites of the Occupy movement, which are global in inspiration, tactics, and connections, leading to an new era of global, national, and local political struggle with unforeseeable outcomes in the Time of the Spectacle. These movements were inspired and connected in certain ways with the North African Arab Uprisings that began an intense year of struggle throughout the world in 2011. History and the future are open and depend on the will, imagination and resolve of the people to create their own lives and futures rather than being passive objects of their masters. Media spectacle is a contested terrain upon which the key political struggles of the day are fought and 2011 was a year rich in examples of media spectacle as insurrection.

End Notes

[1] Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle (1967) was published in translation in a pirate edition by Black and Red (Detroit) in 1970 and reprinted many times; another edition appeared in 1983 and a new translation in 1994. The key texts of the Situationists and many interesting commentaries are found on various web-sites, producing a curious afterlife for Situationist ideas and practices. For further discussion of Debord and the Situationists, see Steven Best and Douglas Kellner, The Postmodern Turn. New York and London: Guilford Press and Routledge, 1997, Chapter 3. On Debord’s life and work see also Vincent Kaufmann, Guy Debord. Revolution in the Service of Poetry, 2006. On the complex and highly contested reception and effects of Guy Debord and the Situationist International, see Greil Marcus (1990) Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century; Tom McDonough, editor (2002) Guy Debord and the Situationist International; and McKenzie Wark (2008) 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International.

[2] See Michael Greenberg, “What Future for Occupy Wall Street?” New York Review of Books, February 9, 2012 at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/feb/09/what-future-occupy-wall-street/ (accessed on February 10, 2012).

[3] See Michael Greenberg, “What Future for Occupy Wall Street?” New York Review of Books, February 9 (as above).

[4] There are a variety of on-line petitions against SOFA including the ACLU’s “Sign the Pledge: I Stand With the ACLU in Fighting SOPA” at https://secure.aclu.org/site/SPageServer?pagename=sem_sopa&s_subsrc=SEM_Google_Search-SOPA_SOPA_sopa%20bill_p_10385864662 (accessed on February 9, 2012) and Broadband for America’s “Hands off the Internet” at http://www.broadbandforamerica.com/handsofftheinternet?gclid=COqHzpuska4CFQN8hwod0GBVew (accessed on February 9, 2012).

[5] There are multiple web-sites devoted to blocking the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline such as the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)’s site “Stopping the Keystone XL Pipeline at http://www.nrdc.org/energy/keystone-pipeline/?gclid=CMX6o7Gtka4CFQVahwodkAwofQ (accessed on January 9, 2012).

[6] There are many Recall Scott Walker sites such as “United Wisconsin to Recall Walker” at http://www.unitedwisconsin.com/jan17 (accessed on February 8, 2012).

This text is extracted from the writer’s forthcoming book, Media Spectacle, 2011: From the Arab Uprisings to Occupy Everywhere! (London and New York: Continuum/Bloomsbury, 2012).

The writer is Chair in the Philosophy of Education at UCLA and is author of many books on social theory, politics, history, and culture, including Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film, co-authored with Michael Ryan; Critical Theory, Marxism, and Modernity; Jean Baudrillard: From Marxism to Postmodernism and Beyond. He is also editing the collected papers of Herbert Marcuse, four volumes of which have appeared with Routledge. His website is at http://www.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/kellner/kellner.html