by Zoltan Zigedy

For nearly three hundred and fifty years, human rights have been important, if not dominant, instruments in the endeavor for social justice. For much of this history, contestants have cited universal rights as marking their position on the field of struggle.

It is equally important to notice that before the seventeenth century, social justice was more often than not contested in a language other than rights-talk.

If Froissart’s Chronicles are to be believed, the Jacquerie of the French countryside and the English peasantry of the 1381 uprising knew no full-blown notion of universal human rights. Instead, they sought to replace unjust lords or appeal to their regent for redress from injustice. It was not their rights that they demanded — for they knew of none — but a measure of fairness or humane treatment.

John Ball, a leader of the English rebellion that came within a deceitful moment of winning peasant “liberation” in 1381, was said to have preached: “We are called serfs and beaten if we are slow in our service to them, yet we have no sovereign lord we can complain to, none to hear us and do us justice. Let us go to the King — he is young — and show him how we are oppressed, and tell him that we want things to be changed, or that we shall change them ourselves.”[1] It was the wisdom and the sense of justice embodied in a higher power appealed to here and not a set of rights, a higher power who would prove treacherous in the end. As a translator of Froissart’s Chronicles, Geoffrey Brereton, affirms, Froissart “uses no word exactly corresponding to ‘equal’.” Rather, he uses “all one” or “all together” for a shared fate. Equality, it appears, is a necessary condition of our modern use of “universal rights” and not witnessed by Froissart.

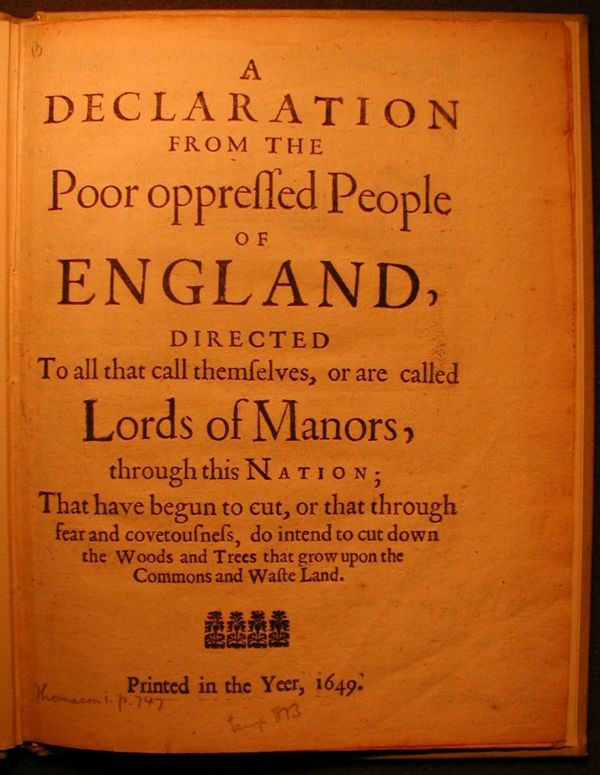

Less than three hundred years later, human rights, universal rights, had established a solid beach head in social justice thinking. Heralding a new age of constitutions (the codification of rights), the English Civil War provoked debates over a world devoid of feudal privilege and divine right. By the 1640’s in England, the notion of “natural” rights — universal in scope — occupied the adherents of militant anti-sovereigns like Cromwell. The Levellers, a radical faction in the anti-crown movement, stood for the equality and universality of human rights.

It was also at this time that an inherent “problem” was exposed with the celebrated doctrine embraced by the seventeenth-century revolutionaries, a problem that lingers to this day. Henry Ireton, a general in Cromwell’s army and a man ill disposed toward the Levellers advocacy of commoners, argued during the Putney Church debates:

All the main thing that I speak for, is because I would have an eye to property. I hope we do not come here to contend for victory — but let every man consider to himself that he do not go to take away all property. For here is the case of the most fundamental part of the constitution of the kingdom, which if you take away, you take away all by that…by that same right of nature (whatever it be) that you pretend, by which you can say, one man hath an equal right with another to the choosing of him that shall govern him — by that same right of nature he hath the same right in any goods he sees — meat, drink, clothes — to take and use them for his sustenance.[2]

This is indeed a simple, but clever argument and one seldom tackled by academic philosophers to this day. Ireton assumes that property ownership (individual, non-equal, non-universal) is historically prior, logically prior, and also sacrosanct in contrast to the “rights” of the radicals. In his view, no one could seriously deny the validity of property ownership. But if we grant that rights exist that have universal and equal applicability and are naturally based, then we must recognize that everyone equally has a right to acquire anything held as someone’s property. Thus, the idea of a universal, equal right to choose who governs cannot be recognized without sanctioning the right to violate property ownership. Ireton is confident that no one engaged in the debate would want that result.

It is this ill-fit of property rights that has always challenged human rights doctrine. It is hard to square the universality of possession as well as the equality of exercise and enjoyment promised by declarations of human rights with the asymmetries and inequalities of alleged property rights. It is difficult to find equality and universality in the distribution of property. Nonetheless, apologists for the right to property have craftily defended it by conflating the inalienability of rights with the inalienability of property (as opposed to the inalienability of the right to property).

Ireton’s second challenge to human rights is the commonplace grounding of human rights in nature. He scoffs at the idea (“whatever it may be”) of rights somehow generated and buttressed only by “nature.” While it may already have been common to speak of “natural rights,” it was certainly strange to a conservative only familiar with rights created by the hand of a being, whether natural or supernatural. That is, Ireton could understand rights generated by convention or dictated by authority (a sovereign or deity). But he found it incredible to accept rights as somehow embedded in nature or revealed through a study of nature. It is just as difficult today to understand “natural rights” in that way.

Early rights advocates and their critics confronted the anomalies inherent in rights doctrines more seriously than modern adherents who simply take the coherence of rights-talk for granted. Richard Tuck, in his essential study of the origins of human rights[3], begins his painstaking history with an account by a Benedictine monk in 1515 who reflects on the stress between a kind of classic rights-talk (ius) and a kind of classic property-talk (dominium).[4] Tuck’s scholarly work demonstrates the insecurities of early rights theorists — a desperate need to show the basis for natural rights outside of supernatural whim or a sovereign’s dictate. In the end they scramble to ground rights in self-evidence or a rational construction from a hypothetical state-of-nature. Grotius serves as an example of the former, a reflexive understanding of rights.[5] Of course Hobbes is an example of the latter.

In our time, philosophers have generally sought to justify human rights through some variant of social contract, the legacy of Hobbes. Consequentialist theories, like utilitarianism, are generally incompatible with or, at least uncomfortable with, social instruments that are both supposedly inalienable and universal. Hence, Bentham’s famous quip that rights are “nonsense on stilts.”

Human rights are problematic because they exhibit peculiar logical features. They are often conceived as counterparts in the moral sphere to laws of nature. That is, they are believed to share universal application with the laws of nature; they are thought to not function only at some specific time and place, but at all times and all places. In the case of the laws that govern bodies at rest or bodies in motion, we might say that they are never suspended. Similarly, the right to speak freely or to travel unfettered are believed to be both inalienable and universal and, therefore, never suspended.

But are they?

Experience teaches that rights often collide with one another. One person’s right to an action may be trumped by another person’s right to do something else, something incompatible with the first action being realized. For example, your right to travel freely may conflict with my right to protect the land that is my source of food. Examples abound in the real world of jurisprudence, examples that require arbitration of conflicting rights. Moreover, when one right trumps another, we may coherently speak of the former as being voided, a mode of speech that suggests that rights are not universal in anyway like the universality of scientific laws. Wendell Holmes’s famous citation of “clear and present danger” as a basis for suspending perhaps the most sacrosanct of human rights, the right to free speech, illustrates the failed analogy with laws of nature.

Those who cling to the notion that human rights are like scientific laws insist that they are discovered or recognized. That is, like the laws of thermodynamics, human rights applied in ancient times even though no one recognized them. Thus, the slaves of the Roman Empire were systematically denied their human rights though no one had yet acknowledged them.

However, this interpretation stretches credibility when we notice that nearly all human rights are socially bound; excepting perhaps the right to life, human rights presuppose social conventions or institutions and surely would have no meaningful existence prior to the creation of those social artifacts. Consider, for example, the right to a free press. What sense would there be to positing this right’s existence prior to the creation of moveable type?

With human rights doctrine and rights-talk dominant in our time, the generation of new rights becomes ubiquitous and ordinary. New kinds of rights (e.g., “entitlements”), an expansion of the subject of rights (to corporations, human remains, fetuses, animals, nature, etc) and extension into new areas (e.g., the internet) are common. While rights-talk is omnipresent in political discourse, its expansion courts dilution and triviality.

The concerns voiced above challenge the smugness of human rights advocates who celebrate human rights doctrines as the final measure of social justice. The objections suggest that justifying human rights or human rights codes is neither obvious nor problem-free; they suggest that the notion of rights is not nearly as coherent as adherents make it out to be; they suggest that the scope or range of rights is neither sharply bound nor bound at all; and they suggest that human rights are contingently constructed instruments that have both a history and an evolution.

It is the last point that opens the way to any serious examination of human rights and their usefulness.

Human Rights and Marxism

Clarity comes with the undertaking of the archeology of universal human rights. Thanks to the careful and scholarly research of Richard Tuck and others[6], we can view human rights as having antecedents (pre-rights, proto-rights), a maturation point (or “watershed”), and continued development. A painstaking sifting through the historical record of rights-talk traces its transformation from an ancient notion of a kind of individual ownership, essentially a private relation between individuals (ius) to a more robust and generalized relation of rights held against everyone and, finally, held by everyone. This evolution coincided fairly closely with the exhaustion and elimination of feudal privilege and the emergence and maturation of capitalist relations of production and distribution.

The implications of this research in the history of ideas escapes contemporary Anglo-American philosophers who dabble on the fringes of the human rights question with marginal matters of fetal rights, animal rights, or corporate rights. Still others wrangle over foundational issues that promise to anchor human rights in the moral universe now and forever. The very idea of human rights as an evolving social instrument best assessed and recommended for its historically determined social efficacy and appropriateness is repellent to most contemporary academic philosophers.

The moral philosopher’s aversion to an empirical, historical approach to rights no doubt springs from a Manichean conflation of the recognition of social and cultural constructs with moral and political relativism, the denial of any kind of validity to rights claims. But that surely is a simplistic, absolutist posture. It is possible to accord validity to individual rights, systems of rights, beneficiaries of rights, and holders of rights at specific times and in specific places. It is far from relativism to grant that rights are useful, even essential, or appropriate depending upon the circumstances. To insist on the absolute universality of applicability, range, and scope of human rights dogmatically invites the problems sketched above.

Perhaps no one saw institutions, practices, and the other artifacts of human history as adaptive, evolving social constructs as did Karl Marx. For Marx, social entities such as human rights were mere epiphenomena for social relations.[7] Put differently, rights-talk is merely a shorthand for a set of conventions linked to a particular era of human history, an era (and set of conventions) defined by the contemporaneous mechanism for providing for the material needs and wants of human beings.

Marx’s strict methodological commitment to the historical method, his consistent search for the social determinants of human institutions and conventions likely explain his brief encounters and dismissive attitude toward human rights. He saw them as artifacts of the rise of the bourgeoisie to be the dominant social force in the modern era. Human rights slogans, codes, and constitutions were the tools for unshackling and promoting this emerging ruling class and its world view.

In Bruno Bauer, Die Judenfrage, Marx understands the rights of man as both canonizing individualism and defining the bounds of social life:

None of the supposed rights of man, therefore, go beyond the egoistic man…that is, an individual separated from the community, withdrawn into himself, wholly preoccupied with his private interest and acting in accordance with his private caprice…The only bond between men is natural necessity, need and private interest, the preservation of their private property and their egoistic persons.[8]

It is in this early formulation that Marx develops the notion of human rights in the service of homo economicus – humans concerned only with their individual, asocial, self interest.

This theme is further developed in a later work, Capital, where the domain of capitalist relations of production is claimed as co-extensive with the domain of human rights. Moreover, they mutually advantage each other: human rights provide the moral and legal (institutional) framework for the “fair” exchange of labor power for wages. And the capitalist mode of production generates and compels the individualism and self-interest essential for the allure of individual human rights.

This sphere that we are deserting, within whose boundaries the sale and purchase of labour-power goes on, is in fact a very Eden of the innate rights of man. There alone rule Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham. Freedom, because both buyer and seller of a commodity, say of labour-power, are constrained only by their own free will. They contract as free agents, and the agreement they come to, is but the form in which they give legal expression to their common will. Equality, because each enters into relation with the other, as with a simple owner of commodities, and they exchange equivalent for equivalent. Property, because each disposes only of what is his own. And Bentham, because each looks only to himself. The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation with each other, is the selfishness, the gain and the private interests of each. Each looks to himself only, and no one troubles himself about the rest, and just because they do so, do they all, in accordance with the pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all-shrewd providence, work together to their mutual advantage, for the common weal and in the interest of all.[9]

It is the intimate linkage of human rights and the capitalist mode of production that define Marx’s view and the Marxist understanding of the ascendency and ubiquity of rights-talk in political discourse. For Marxists, declarations and codifications of human rights are inseparable from their role in bourgeois society, their place in the social fabric of capitalism. Human rights doctrine serves as a secure and compatible foundation for morality, law, and politics in the ascendency and maturation of the capitalist mode of production. Friedrich Engels summarized the Marxist opinion of human rights in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific:

The great men, who in France prepared men’s minds for the coming revolution, were themselves extreme revolutionists. They recognized no external authority of any kind whatever. Religion, natural science, society, political institutions – everything was subjected to the most unsparing criticism: everything must justify its existence before the judgment-seat of reason or give up existence. Reason became the sole measure of everything. It was the time when, as Hegel says, the world stood upon its head: first in the sense that the human head, and the principles arrived at by its thought, claimed to be the basis of all human action and association; but by and by, also, in the wider sense that the reality which was in contradiction to these principles had, in fact, to be turned upside down. Every form of society and government then existing, every old traditional notion, was flung into the lumber-room as irrational; the world had hitherto allowed itself to be led solely by prejudices; everything in the past deserved only pity and contempt. Now, for the first time, appeared the light of day, the kingdom of reason; henceforth superstition, injustice, privilege, oppression, were to be superseded by eternal truth, eternal Right, equality based on Nature and the inalienable rights of man.

We know today that this kingdom of reason was nothing more than the idealized kingdom of the bourgeoisie; that this eternal Right found its realization in bourgeois justice; that this equality reduced itself to bourgeois equality before the law; that bourgeois property was proclaimed as one of the essential rights of man; and that the government of reason, the Contrat Social of Rousseau, came into being, and only could come into being, as a democratic bourgeois republic. The great thinkers of the 18th century could, no more than their predecessors, go beyond the limits imposed upon them by their epoch.[10]

Thus, human rights are elements of a world view — a superstructure, if you will — spawned by the emergence of capitalism and sustained by it. Individual rights, inalienable and universal, constitute the moral, legal, and political framework most compatible and agreeable with the capitalist system.

That is not to condemn human rights, but to place their emergence and development in the context of the emergence and development of capitalism. Insofar as capitalism was a liberating force, human rights counted as the basis for a more just and liberating society. The emancipation of the bourgeoisie was, in important ways, a giant step in the emancipation of the masses, the advance of working people. In fact, declarations of and constitutions acknowledging human rights inspired millions to struggle for greater participation in civic and political life in bourgeois republics. The call for human rights has served the fight against the bondage of slavery, the struggle for universal suffrage and many other essential reforms. While these reforms often draw upon human rights, they only go so far as to “perfect” and “complete” the promise of the bourgeois epoch. They do not challenge it.

Understanding and Misunderstanding the Marxist Critique of Human Rights

Marxists have never been hostile to human rights doctrines per se. They have, however, criticized the fetishism of human rights and denied them unique status as the sole or central arbiter of morality and social justice. They have disputed their authority for all times and for all places.

Throughout the twentieth century, Marxists have couched many radical demands in the language of rights, from unionization campaigns to national self-determination. Communists have fought for the right to a fair trial for many victims of prejudice and injustice. They have been prominent among those who have advanced the cause of the civil rights of racially and nationally oppressed groups. And they have fought for their own rights to free association, speech, and the dissemination of ideas.

Most significantly, Communists have been decisive in enriching human rights declarations after the Second World War to include positive rights to employment, shelter, welfare, and the many other rights that are constitutive of economic justice. Certainly some New Deal liberals and European social democrats supported these social rights as well, but the Soviet Union and other socialist countries advocated for the most robust and complete social rights while representatives of capitalist countries sought to limit rights declarations to individual rights protective of actions, space, and property.

Socialist countries also took the lead in pressing the decolonization process through international agreement on the right of a nation or people to self-determination, a right not eagerly welcomed by colonial powers and their allies.

While rights declarations proliferated after the Second World War, they increasingly reflected Cold War differences, radical differences in world-view. More and more, covenants and declarations expressed ideological positions shaped by the balance of forces in international bodies like the UN. This stage in the evolution of human rights doctrine became a battle ground staked out by advocates for socialism and advocates for capitalism. Of course it was not postured as such in the capitalist West, but as a struggle between those respectful of human rights and others who trampled them. Thanks to Cold War ideologues like Isaiah Berlin,[11] human rights came to be identified with the set of rights compatible with the capitalist order and the middle classes.

To my knowledge, no human rights campaign has ever been mounted by the human rights establishment in defense of Article 25 of the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the article that guarantees “a standard of living adequate for the health and well being…including food, clothing, housing and medical care, and necessary social services.”

Whether they sprung from sincere motives or not, human rights organizations flourished during the Cold War with generous overt support from well-off supporters, foundations, and even corporations. Covert support from Western security services were suspected as well. Interestingly, some of today’s more prominent rights-based NGOs (The International Republican Institute, The National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, National Endowment for Democracy, International Foundation for Electoral Systems, etc) are very thinly veiled conduits for US government funds. That the evolution of human rights has been shaped by large and biased political considerations is unquestionable. That advocacy has been tainted, compromised, and corrupted on many occasions is equally unquestionable.

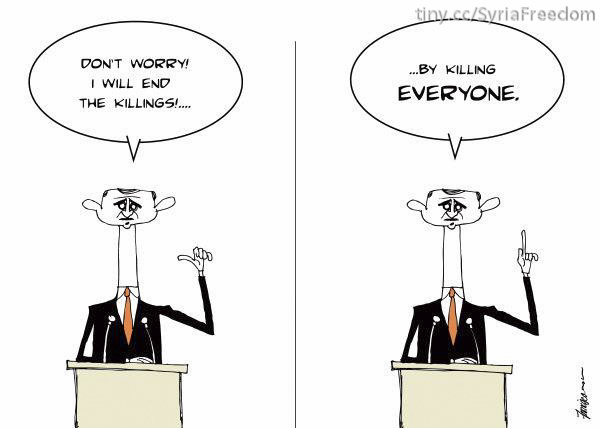

Since the demise of the European socialist community, NATO and its capitalist masters have tarnished the reputation of human rights doctrine by dismantling Yugoslavia, destroying Libyan civil society, and now threatening Syrian sovereignty, all under the banner of human rights. While tens of thousands have died in these violations of the fundamental rights to self-determination and non-interference, the human rights establishment has been largely silent about both the human costs and the attendant hypocrisy.

When human rights became a crucial weapon in the West’s Cold War struggle with the Soviet Union, the Western powers went to great lengths to showcase the civil rights enshrined in their respective liberal constitutions. Side-stepping the limitations on freedoms of action imposed by economic inequality, these regimes conjured a picture of the carefree expression of speech, unlimited travel, and personal success.

An example of the efficacy of human rights as a political weapon emerged early in the Cold War. Socialist construction of Eastern Germany produced tens of thousands of educated, trained, but modestly compensated professionals. The less egalitarian West enticed many to leave the East for opportunities to grow personally prosperous. Given a common language, culture, and proximity, “defecting” came at little cost. Not only did this tactic drain the East of skills, but it also effectively stole the resources devoted to professional training, and eroded any sense of social solidarity. Faced with mounting losses, the East built the infamous Berlin Wall. While the East owned a credible explanation for the Wall, the US and its allies voiced outrage at the violation of human rights. The absolutism of human rights proved to be a powerful foil to the practicality of the Wall. The lesson was well learned by Western propagandists.

Of course the West failed the test of consistency. Human rights were an obvious embarrassment to Western powers who maintained friendly and close relations with regimes that were scornful of human rights, but resolutely anti-Communist. Instead of hostility, the US retained close links with the apartheid regime in South Africa under the hypocritical policy of “constructive engagement” as well as other despicable governments.

And since the end of the Cold War, the US and many of its allies have shed the pretense of bastions of human rights, a tacit admission of their service to Cold War goals. The creation of a “big brother” state by the Bush administration and its further development by the Obama administration in the US underscores official cynicism about human rights to privacy, speech, and association. And the quiescence of the major human rights organizations to this development reeks of hypocrisy. The claimed surveillance of civil society by the so-called “totalitarians” of the past pale in comparison with the technological means available to and in actual use by the US national security apparatus.

Yet the Marxist criticism of human rights is not limited to the charges of inconsistency, special pleading (hypocrisy), and cynicism. Marxists also object that human rights doctrines often crowd out other worthy counter-doctrines. Whether a constitution of human rights can be constructed without the right to property and its sanctity is for others to decide. But the fact is that the so-called right to property has constituted the fundamental obstacle to acceptance of the Marxist counter-vision. The rise of capitalism gave birth not only to human rights doctrines, but a counter-instrument of social justice: the concept of labor exploitation. A trip to the Oxford English Dictionary will reveal that the English usage of “exploitation” in its application to humans coincides roughly with the ascendency of industrial capitalism and especially advocacy for labor.

While Karl Marx neither planted the idea or first used it in defense of workers, he and Friedrich Engels undoubtedly made it a centerpiece of radical social criticism and placed its elimination at the top of working class goals. For most of the modern era, the elimination of exploitation of man by man has stood as the primary slogan of the working class movement.

But eliminating exploitation intersects and conflicts precisely with the absolute and unalienable right to property. In the Marxian sense, exploitation is the logical consequence of the private ownership of the means of production; there could be no persistent and systemic labor exploitation (in the Marxist technical sense) without the institution of private property and its set of protective rights.

It is this intersection that generates a class divide between human rights advocates and revolutionary working class partisans. Throughout most of the developing world, most people pay little or no heed to the call for freedom of the press, travel, dissent, or property when they lack the rudimentary means of exercising any of those rights or most others constitutive of the human rights canon. They see instead the extremes of wealth and poverty as obstacles to the satisfaction of their basic needs, even survival. They see their tenuous hold on life not enhanced by bourgeois rights, but only by a radical reordering of economic relations. And the call for the elimination of exploitation is the highest expression of this understanding.

It is imperative to understand that classic bourgeois human rights, as negative rights, as formal, procedural rights to liberty, offer little to those lacking the means to act under their protection. Their celebration by the relatively well-off — the middle and upper classes, especially of the economically advantaged nations — is not shared by those economically beneath them. However, this takes nothing away from their worth. Like great and unique works of art, everyone appreciates their existence, but few draw much solace from them in the daily struggles of life. It is this reality that escapes the human rights establishment and narrows their campaigns. Their stubborn refusal to embrace positive rights to shelter, sustenance, employment, access to health care, etc. into the human rights canon trivializes their commitment to social justice and opens them to the charge of special pleading. Their dogmatic focus on individual rights and willful blindness to social, cultural and national rights, like the right to self-determination, invite compromise by institutions hostile to the latter.

Like all instruments contrived by humans, human rights are only as useful and just as those who wield them.

End notes:

[1] Froissart, Chronicles, ed. and trans. By Geoffrey Brereton (London, 1978) p. 212.

[2] Quoted in Freedom in Arms, edited by A.I. Morton (New York, 1975) p 43-44.

[3] Tuck, Richard, Natural Rights Theories: Their Origin and Development (Cambridge, 1979).

[4] Tuck, p 5.

[5] “…and just as animals by union of male and female seek the propagation of their species and provide for their young; so it is that man, doing the same, is conscious of doing what is right…” quoted in Tuck, p. 68.

[6] Tuck, Richard. Natural Rights Theories: Their Origins and Development (Cambridge, 1979); Finnis, J. Natural Law and Natural Rights (Oxford); Rights, White, A. R. (Oxford, 1980).

[7] Expressed most cogently in his exposition of the fetishism of commodities. Capital, (New York, 1906) vol. 1, ch. I, section 4.

[8] In Karl Marx: Early Writings, trans. and ed. by T.B. Bottomore ( NY, 1964) p. 26.

[9] Capital (New York, 1906), vol. I, chapter vi, p. 195.

[10] Engels (Moscow, 1954) p. 33, 35.

[11] See his Four Essays on Liberty (Oxford, 1969).

[Thank you indeed ZZ for this insightful piece]

Zoltan Zigedy is the nom de plume of a US based activist in the Communist movement who left the academic world many years ago with an uncompleted PhD thesis in Philosophy. He writes regularly at ZZ’s blog, and on Marxist-Leninism Today. His writings have been published in Cuba, Greece, Italy, Canada, UK, Argentina, and Ukraine.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change. Thanks for your support.

One thought on “Human Rights: A Marxian perspective”

Comments are closed.