May memory restore again and again

The smallest color of the smallest day:

Time is the school in which we learn,

Time is the fire in which we burn.— Delmore Schwartz, “Calmly we walk through this April’s day”.

Art is about controlling time.—Francis Ford Coppola on his film Megalopolis.

by Sanjay Perera

WHEN the history of cinema is written a hundred years from now Francis Ford Coppola will be remembered not only as an auteur but as one the greatest and most influential of filmmakers. His latest, 40 years in the making, Megalopolis: explores time and art, the move from dystopia to possibly utopia, and trenchant social commentary. But it is much more. In an outstanding interview Coppola said he wanted to make a film with so much in it that it would be talked about for years as much as Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (a most challenging work). While it is crammed full of references and symbolism that make the film fascinating, it did receive poor reviews; not only did it tax viewers raised on a diet of superhero sequels, action blockbusters, tedious remakes, mind-numbing horror movies: it was probably unappreciated because of its honest and astringent take on the decline of American society (and many others).

Among Coppola’s unforgettable and extraordinary films are The Conversation, The Godfather trilogy, Apocalypse Now (one of the truly original films of the 20th century), and the underrated masterpiece Youth Without Youth. His complete version of Apocalypse—Apocalypse Now Redux, is a masterwork of cinema. But his films have been also criticised and had problems getting support in being financed and made; yet they won many awards and are regarded as modern classics. Perhaps none of his movies was panned more than Youth Without Youth which explores time and consciousness; it is his most metaphysical film.

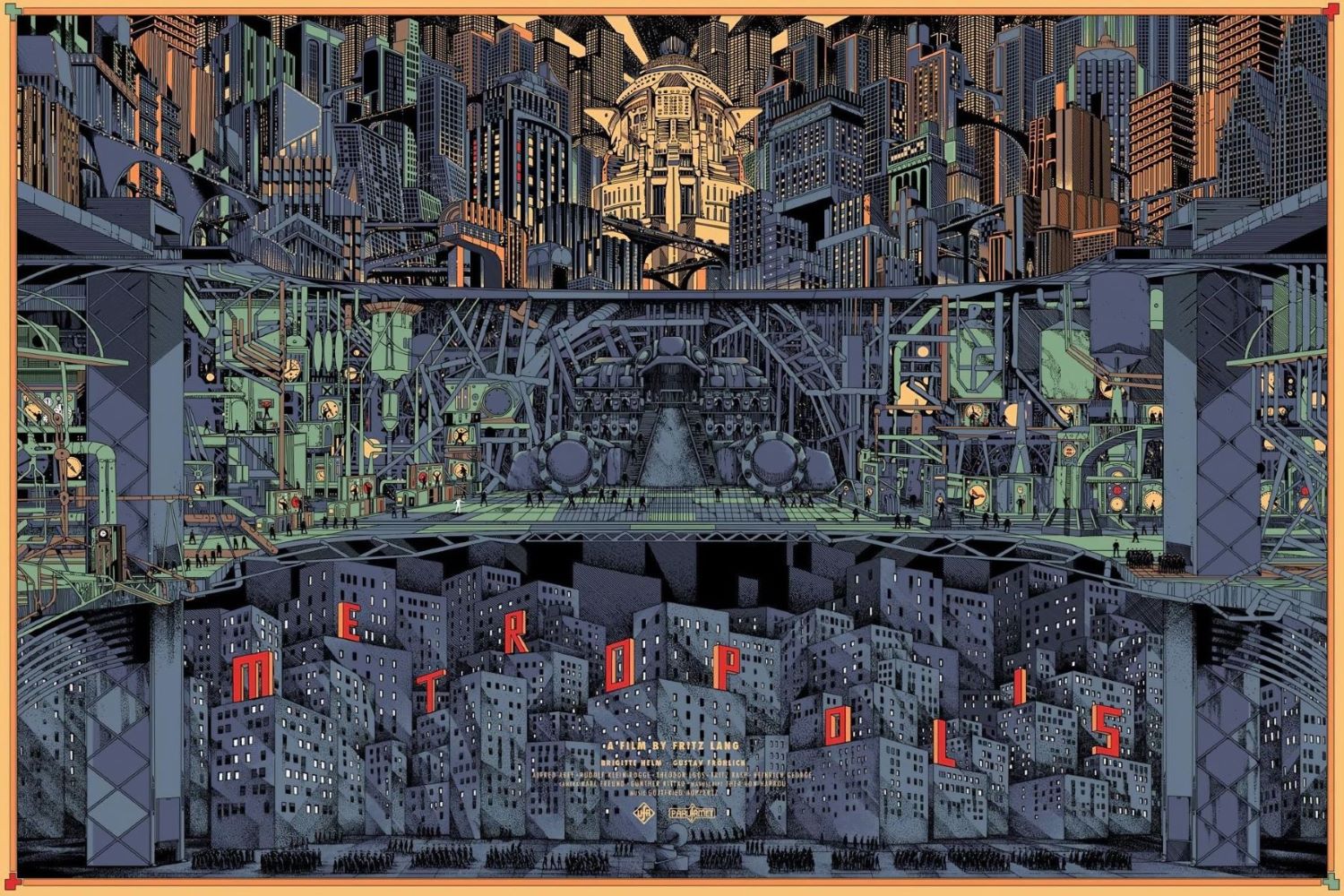

There are many references in Megalopolis to film, literature, art, history, politics and the nature of civilisation; the film also melds elements of fantasy and science fiction making it hard to classify. It is experimental, in a way a pure form of cinema, and Coppola wants to reinvent the way film is done and interpreted; naturally, this results in resistance and misunderstanding. The film makes references to The Matrix, Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, and even The Hunger Games (among many others). Most of all it engages with one of the iconic films of cinema Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Lang, an Austrian who left for the US with the rise of the Nazis, created many cinematic landmarks. But his 1927 film Metropolis (together with M. from 1931) has been subject to endless interpretation and influenced many filmmakers.

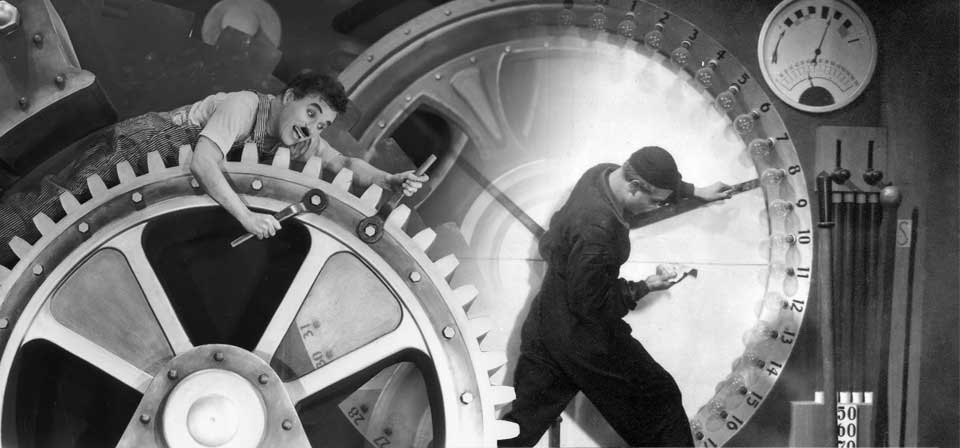

Metropolis, a futuristic version of New York (just like Megalopolis), also deals with a Germany that was recovering from WWI and heading inexorably into the next war. It has rich subtexts filled with biblical significance, and a messianic theme; it further takes a sharp look into the relations between labour and capital; the exploitation of the working class by the ruling elite. It clearly impacted Chaplin’s great film, Modern Times (1936). While the machine in Metropolis is depicted as Moloch consuming the workers, the machine in Modern Times dehumanises people (often hilariously) and turns them into mechanistic beings. It is a move from a blatantly spiritual subtext in the 1927 film to the more industrially influenced film of 1936 as the world edged into the next global war. However, while Chaplin’s film showcases a poignant closing scene without closure, Lang’s reaches for some form of redemption with its renowned line: “The mediator between head and hands must be the heart”. The film has less ambiguity in that sense than Chaplin’s as it implies unity and collaboration between people and the ruling class is possible sans alienation between the individual, society and the elite that is apparent in Chaplin.

With Megalopolis, the utopia proposed as the alternative to a state of dystopia that some may recognise, implies a new way forward from a world tired of war and disease; misuse of wealth, power, and technology; an inane celebrity culture. A new civilisation is proposed that hearkens to ideas towards genuine progress, rehabilitation; engendered by proper use of technology, constructive political will, positive thoughts and memories, compassion. And in the film’s metatextual reference to itself and other movies: the potential deliverance of humanity through art. Then there is the science fiction element literally in the form of what the protagonist, Cesar Catalina (brilliantly portrayed by Adam Driver), discovers but is never quite explained: Megalon. The latter is a magical-like substance that can stop time, heal injuries, make people almost invisible, and create wonderful self-sustaining material for anything, including buildings and homes. And even more.

From a historical perspective, Coppola wants to draw a clear line between the Roman republic and the American one and show that the latter, like its historical predecessor at the end, is in its last stages in need of a reboot, a radical paradigmatic shift—to survive. He reached back into Roman history to draw a parallel to contemporary times, and so key characters are named Catalina, Cicero and Crassus who have actual historical counterparts in ancient Rome: Lucius Sergius Catilina, Marcus Tullius Cicero, and Marcus Licinius Crassus, respectively. The Roman personages were players in what is known as the Catilinarian conspiracy; an attempted coup d’état by Catalina to remove the consuls Cicero and Antonius. In the film, while antagonism exists between Catalina (visionary architect and Chairman of the Design Authority) and Cicero (mayor of New Rome/New York), Crassus owns all the banks and influences both sides: yet it only reflects loosely past events as Coppola exercises much creative license in his version.

In Megalopolis, Catalina wants a new world created with Megalon, and Cicero represents the old order and politics, wary of change. Conspiracies abound, there is unexpected but clever humour, visual dazzle, violence and hedonism; but Catalina’s obsession is Time. He is haunted by the death of his wife and wants to stop time; relive certain moments and freeze himself in that process forever; undo the past if he can but realises he cannot. Here there is a reference to Nolan’s Inception but Coppola takes it further. Cicero’s daughter provides the new love that allows her to use the qualities that emanate from Megalon as well, for what activates its effect on time is the heart. What is equally noteworthy is that Coppola reaches back to the preservation of memory in time that is not only archetypal but opens pathways of connection to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. In its thematic development of time, the film moves into another dimension; its creative editing manipulates time and gives it a hallucinatory effect that not all viewers would resonate with. But therein lies its wonder.

Ultimately, apart from a new world Catalina wants to create the ability to relive his past and remain there, at least in his mind, for it is where his happiest memories reside. Coppola’s statement about art controlling time is a corollary of the entire Proustian project. It goes beyond the standard manipulation of time by speeding up motion in scenes, slow motion, and the use of dissolves from one scene to the next. He cast actors he wanted in his film when he first planned it decades earlier like Laurence Fishburne and Jon Voight, now much older like himself, in its final realisation. He could not preserve himself and them in time but kept them in his vision just as he dedicated the film to his wife of 60 years that passed on earlier this year who journeyed with him in making the film. To see a clearer connection with Coppola’s intention and Proust: paintings, pictures, images—are the best example of a moment in time and space kept in a certain state of perpetuity reliving that moment: but open to interpretations beyond what the artist could have imagined. The visual arts, and its discussion, is crucial to the vast cathedral of words Proust deploys to give permanence to his artistic vision. And this yet again connects Marcel Proust directly to what literary theorist Maurice Blanchot wrote.

However, apart from perhaps Coppola, the filmmaker most obsessed with Time was the legendary Andrei Tarkovsky: a genuine visionary, experimental, and certainly the most poetic of directors. Tarkovsky’s groundbreaking work for the most is preoccupied with time and capturing the lyricism of the moment even in time of war. His films range from the dramatic, historical, the common; all with a touch of fantasy and at times, science fiction, with many surrealistic moments. But they are intensely spiritual. Again, his concern is time, memory, art, the nature and essence of cinema. Perhaps the filmmaker closest to Proust’s sensibility though connected to his Russian roots. Each frame of film is a moment of time captured, and the moments— carefully constructed and envisioned in motion—are the film, like consciousness. In his impressive book Sculpting in Time (1985), many insights are shared:

The filmmaker is a sculptor, moulding time and space.

Cinema is the art of time, the art of sculpting time.

From the first moments of cinema, filmmakers have been striving to capture the flow of time.

Coppola would agree with all of this as Megalopolis grapples with the ideas expressed in those statements. And Megalon is used to try and control, manage, and mould time into what Catalina wants though he does not always succeed after a crisis, until he finds love again. This reiterates the theme of Metropolis of the heart being the mediator between the head and the hands; the heart unites the world of abstraction that Catalina occupies but it is the love he rediscovers in Julia that keeps him grounded as she reaches out to him.

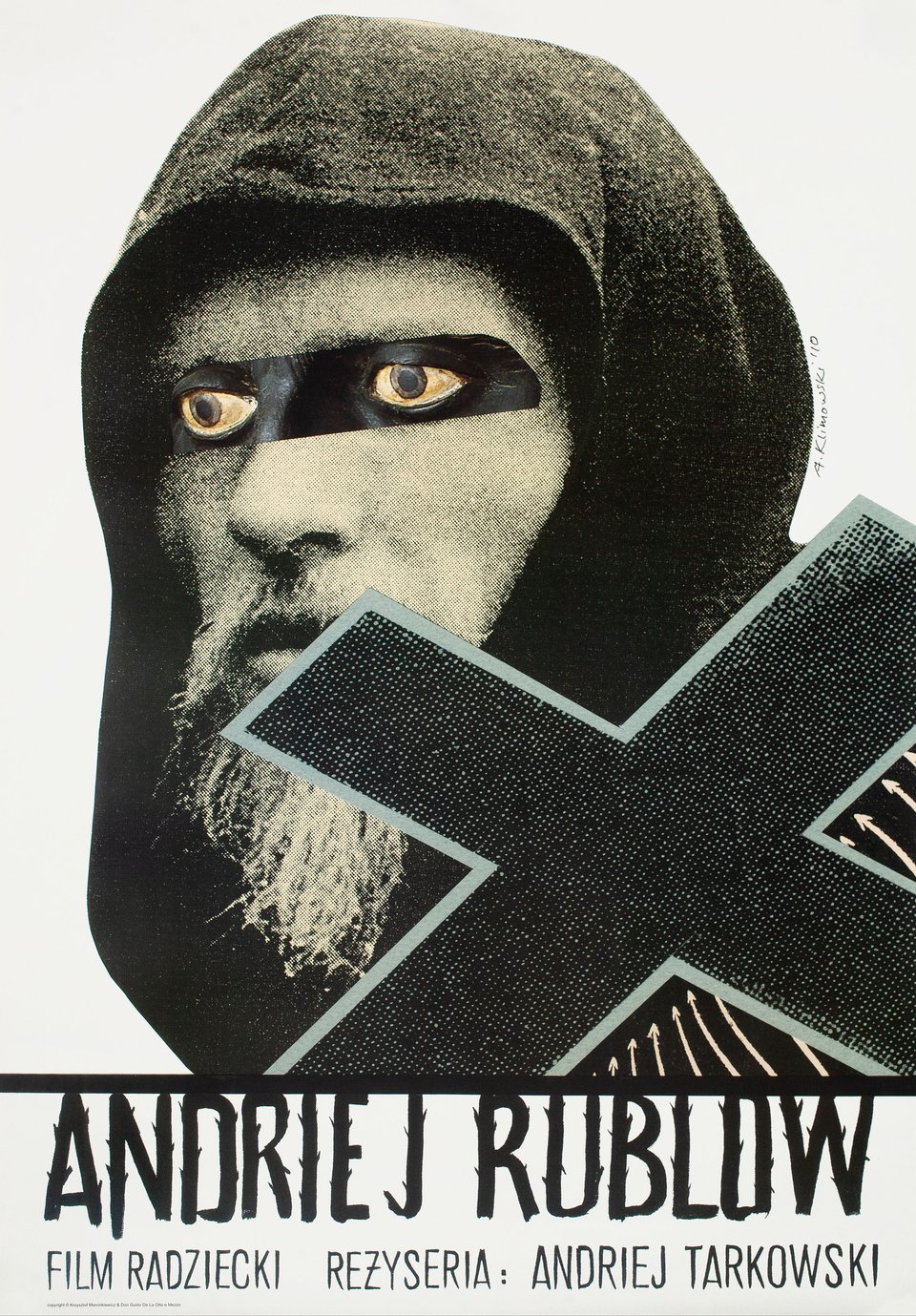

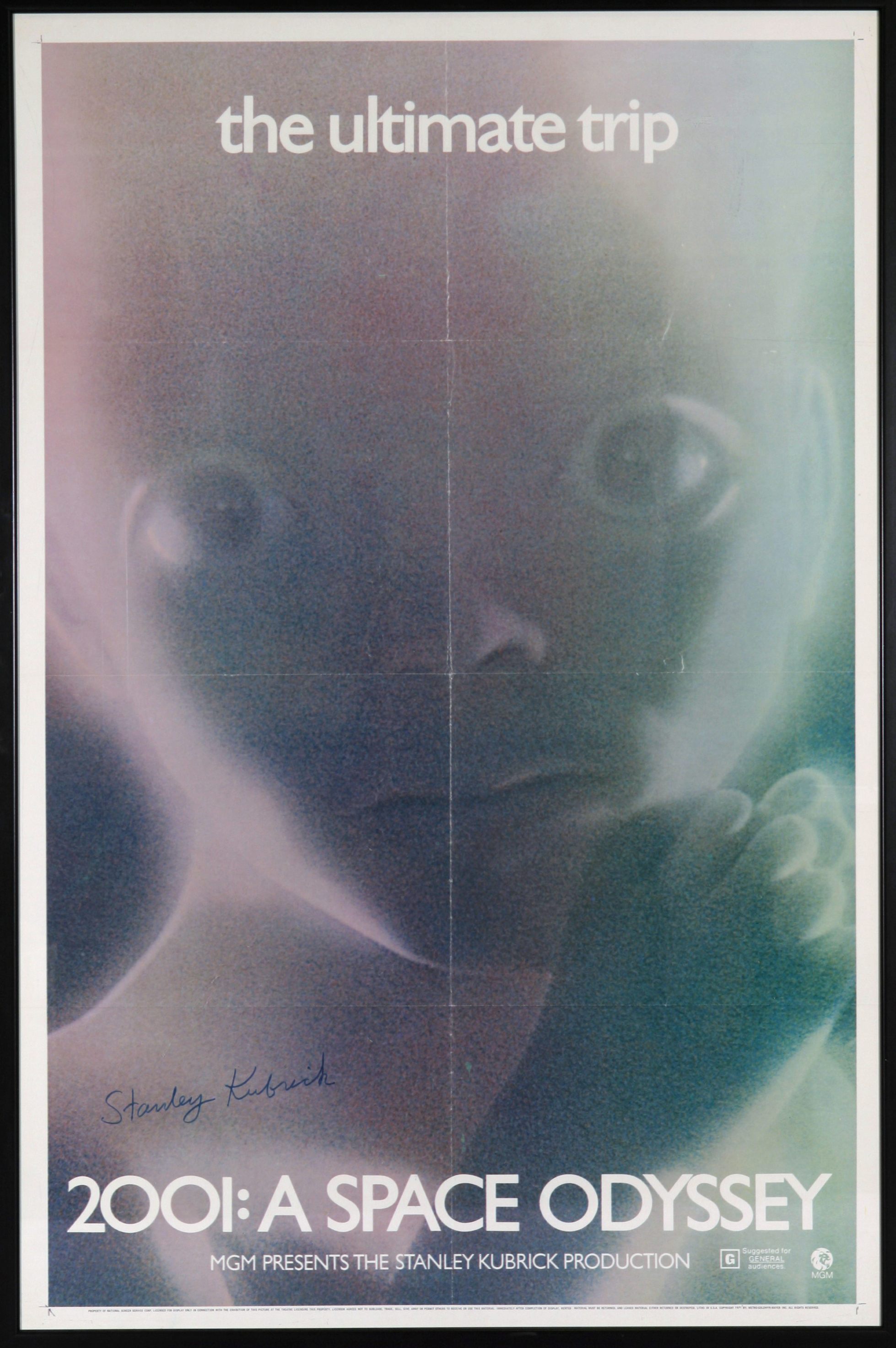

The force of memory and insistence on reliving for as long as possible a moment that is important, filled with affection and the redemptive, abounds in Tarkovsky’s work. Much of the potency of his films stem from his struggle to express his vision under the censorious eye of the repressive Soviet regime; the problems he faced led him to leave and make his final film in exile in Europe, dying in Paris. The sense of being absolved and uniting with the Ultimate as part of atonement is memorably captured in many images in his films. Among the numerous haunting moments in his films, a particularly striking one, is at the end of the 1972 film Solaris (his response to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey); it has a final scene of redemption that is controversial as it is powerful. That final image in the film, representing obsessing over a significant and symbolic moment in time, and holding onto it for infinity is certainly examined in Proust.

No other art can compare with cinema in the force, precision, and starkness with which it conveys awareness of facts and aesthetic structures existing and changing within time.

Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time.

In a posthumous work written at the turn of the 20th century, Jean Santeuil, Proust produced a dress rehearsal for his monumental In Search of Lost Time. The former is again, based on the earlier years of the author’s life but was deliberately left unpublished; it is about 800 pages long and incomplete; it only saw publication in the early 1950s. It is a wonderful primer for those who seriously want to engage with his later work. There are remarkable passages that deal with and foreshadow the obsession of time, memory, and art as the essence of being. While the book deals with a young man, the analogies and images drawn by Proust extend through many circuitous lines into different ideas that he pulls together into an elaborate tapestry of memory, of an instance vividly imagined then dissected: at times almost clinically, which would be his signature style. An example of this from Jean Santeuil:

In life (even more than in the theatre) there is something that defies description in the way a father or a mother looks, whose life is drawing to a point in which all that matters is to gaze with love and sadness at a daughter—sadness that is born not so much of the knowledge that soon the time of gazing will be over as because it is inevitable for one who loves another wholly for that other’s sake and, being conscious of what is essential in his own life, is conscious, too, of sadness. And so it is that the way in which fathers and mothers look at a child, with tender criticism, silent admiration, melancholy love and an infinite but unrealized yearning for the happiness they wish her to have, is always, so to speak, a vague gazing into space, sometimes accompanied by a movement of the head which is partly the twitching of old age, partly an attempt to express feelings for which there are no words and expresses doubt, criticism, discouragement and uncertainty, though the look in their eyes speaks only of love.[1]

The lines from Proust are like a painting, the countless images that Proust admired and pondered over his entire life: but it is not merely looking at a picture, a tableau, an image enshrined in the mind; it is a reliving constantly of all that went into a moment; the thoughts, sentiments, emotions; how they may be projected in time are enacted in minutiae going beyond imitation, simulation; it is an actual process of living through it again. That is why some can look at paintings or pictures for hours, read or re-read lines, pages or entire books over and over again, or watch a film many times through the years. An eternal recurrence.

In a penetrating essay on Proust, “The Experience of Proust”, Blanchot writes[2]:

Time: a unique word in which are collected the most varied experiences, which Proust distinguishes, certainly, with his attentive probity, but which, overlapping, are transformed to make up a new and almost sacred reality. Let us recall only a few of its forms. First real, destructive time, the terrifying Moloch that produces death and the death of forgetfulness. (How can one trust such a time? How could it lead us to anything but a nowhere, without reality?) Time, and this is still the same, that, by this destructive action, also gives us what it takes away from us, and infinitely more, since it gives us things, events, and beings in an unreal presence that raises them to the point where they move us. But that is still nothing but the chance of spontaneous memories.

The paradox of time that gives us all that terrifies and delights is what we are trapped in from birth to death; birth which most of us celebrate and death that is usually afeared. Time provides us with the opportunity to learn from our mistakes and seek betterment; existence is that time and space which is the “school in which we learn” and indeed, as we gain in experience and walk our path of atonement: it is “the fire in which we burn” and purify, as the lines from the epigraph state. In an eldritch moment in Metropolis, the machine transforms into an image of Moloch as workers are shown to be marching into its fiery mouth; humans are sacrificed to keep The System going; and the machine that supports the functioning of the infrastructure of The System is operated constantly by different individuals through work shifts: who turn the hands of the large clock-like device; the operator is like Atlas burdened by the weight of the world (see composite stills of Modern Times and Metropolis above). It is, moreover, an allegorical reference to the turning hands of time that consumes us as we burn our life away through the daily grind.

It is this all-consuming Chronos that Proust struggles with as he retells his life to the point he becomes a writer; moments and experiences he enshrines in his mind, and through language, for posterity: so as to break free from the bonds of time, keep his thoughts alive through the memory of readers he will never know so that it is always alive in consciousness. That is what Catalina/Coppola/Tarkovsky try to do with their experiments to halt time and relive moments of love to efface those of loss and tragedy: to keep our own ideas alive through the consciousness of others.

Blanchot continues with (italics Blanchot’s):

Proust also experienced the incomparable, unique ecstasy of time. To live the abolition of time, to live this movement, rapid as ‘lightning,’ by which two instants, infinitely separated, come (little by little although immediately) to encounter each other, joining together like two presences that, through the metamorphosis of desire, could identify each other, is to travel the entire extent of the reality of time, and by traveling it, to experience time as space and empty place, that is to say, free of the events that always ordinarily fill it. Pure time, without events, moving vacancy, agitated distance, interior space in the process of becoming, where the ecstasies of time spread out in fascinating simultaneity—what is all that, then? It is the very time of narrative, the time that is not outside [hors] time, but that is experienced as actually outside [dehors], in space, that imaginary space where art finds and arranges its resources.

Here Blanchot moves Proust, and we bring Coppola along, into his own theoretical framework analysed earlier in his renowned The Space of Literature. As Blanchot explains, the work upon completion does not need the author and exists on its own; the absence of the author is necessitated, and he is metaphorically dead (and over time, literally), for the work is appreciated in time but exists in a creative space; and almost like the effect of Megalon, it is where artistic truths not only find and validate themselves: but are rearranged or synthesised to meet the highest good of all. It is a moral and creative space working with, and against, the ineluctable destructive nature of time. It is indeed paradoxical. Tarkovsky would agree for in many of his films time and consciousness are reflected in the changing film stock: scenes move from black and white to sepia to colour in the same film. The changes correspond to different states of mind and are meant to invoke different modes of thought; they try to draw a richer reaction emotionally, intellectually, spiritually, from the viewer. But in the changing film stock, he consciously manipulates time for the black and white scenes or those in sepia also indicate temporal difference, just as colour does: there is a shift and blend of past, present and future, and in some instances, a merger. The film itself occupies its own artistic space-time to be appreciated through the ages for as long as it lasts, and there are people to view it. Tarkovsky controls time: what Coppola does, but perhaps at times (pun unintended) in an obvious way.

And Blanchot adds,

He [Proust] does not see in it the simple pleasure of a spontaneous memory, since it is not a question of a memory, but of ‘the transmutation of the memory into a directly felt reality.’ He concludes that he is faced with something very important, a communication that is not of the present, or of the past, but the outpouring of the imagination in which a field is established between the two, and he resolves henceforth to write only in order to make such moments come to life again, or to respond to the inspiration that this transport of joy gives him.

.

This is, in fact, impressive. Almost all the experience of Le temps perdu [Lost Time] can be found here: the phenomenon of reminiscence, the metamorphosis it presages (transmutation of the past into the present), the feeling that there is here a door open onto the domain unique to the imagination, and finally the resolution to write in light of such moments and to bring them back to light.

This is central to Proust and many artistic works that study time. The memory, the image, helps to create a reality, simultaneously an alternate and present one: it is multidimensional. Proust recalls and reimagines his life, and through the persona of the narrator relives it. In fact, that is the reality he chooses to try and live in as the life outside of the work is what he does when he is not writing but as the work exists in its own space-time he is absent from it though in a way he lives through it. Tarkovsky’s many poetic images and scenes as in Solaris and Stalker (both technically science fiction, the latter is difficult to classify) show weeds, plants floating in streams; objects like weapons and other items that represent human activity contra nature also appear in the flowing water (the flow of time) and are shot with long takes as verse is read in voice-overs to the accompaniment of Bach. They provide a sense of solitude, meditativeness and contemplation reminiscent of Proust. The scenes of nature are always introspective, positive, healing; those of human mechanical invention, jarring in juxtaposition. Similarly, in Megalopolis the re-envisioned and rejuvenated New Rome of Catalina’s has greater natural landscape intertwined with human dwellings and workplaces; Megalon replaces alienating dehumanising steel and concrete constructions. It is a self-sustaining ecosystem that thrives, and is conducive to healthy and meaningful living.

Modern mass culture, aimed at the ‘consumer’, the civilisation of prosthetics, is crippling people’s souls, setting up barriers between man and the crucial questions of his existence, his consciousness of himself as a spiritual being.

Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time.

In contradistinction to long takes by Tarkovsky—like the meandering sentences and paragraphs that go on for pages in Proust—Coppola’s film has frequent changes of scenes and fast editing cuts interspersed with surreal images that evoke a state of mind that is troubled (Catalina’s), and a society in decay, utterly corrupt; a populace that lacks focus and purpose, dumbed down, open to demagoguery. The images move in a manner that mirrors the lack of harmony between people and the world they are ruining. But Coppola then creates an amalgam of past, present, and a future with its possibilities and modalities in sequences that can make viewing a further challenge: but like a Pynchon novel, especially Gravity’s Rainbow, it is a matter of letting go and allowing the artistic hallucinogen kick in.[4]

Notwithstanding, the pace of the film does reach a point when it briefly slows down, and when time stops in moments of harmony, unity and understanding. The final shots particularly the penultimate one, reflect this, where two couples are motionless in time and the focus is a child: the one that moves forward into the future. The couples are as in Proust reliving that moment of joy, fixed in time. For when there is a union of souls and happiness, time seems to stop. Time is captured, regained, controlled, and well-nigh non-existent. Just as the baby at the end of Megalopolis also signals a form of victory over time as life is renewed and continues, the last scene of Kubrick’s 2001 is the Star Child who is messianic and heralds a new world: a victory over the past failures of humanity and its controllers, the end of destructive time and the start of a golden age.

The purpose of controlling time via art is to have the best moments, the positive, kept alive for as long as possible and to then unfurl them in consciousness living through what gives the greatest happiness, satisfaction and meaning, over and over again: a datum for everything else that comes after that should be even better. A series of the best moments like the frozen single frames of a film that move in succession ad infinitum as the movie of consciousness.

The Japanese term Komorebi is significant: the core of Wim Wenders’ transcendent Perfect Days. It means the shimmering of light and shadows that is created by leaves swaying in the wind. It exists only for a moment, the perfect time of day, or that moment of complete rest and tranquility irrespective of what happened or goes on around us. The use of art to control time, and have controlled time as artistic representation, is an extension of Komorebi made into a moment of gratitude that lasts eternally. It is in a way, what the baby at the end of Megalopolis represents, the Star Child in 2001 signifies, and the closing scenes in Solaris and Tarkovsky’s masterwork Andrei Rublev embody: that which goes even beyond earthly love, redemption, liberation, and happiness; it is salvation and life eternal.

But sometimes illumination comes to our rescue at the very moment when all seems lost; we have knocked at every door and they open on nothing until, at last, we stumble unconsciously against the only one through which we can enter the kingdom we have sought in vain a hundred years―and it opens.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time.

[The iconic song with apposite lyrics from the 1990s at the end of the film.]

End notes:

[1] P42-43. Proust, Marcel, Jean Santeuil. Translated by Gerard Hopkins, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1956.

[2] P25-38. Blanchot, Maurice. “The Experience of Proust”, The Book to Come. Translated by Charlotte Mandell, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2003.

[3] The still from Stalker is similar to scenes in many Tarkovsky films: plants, fauna, living things, and man-made/artificial objects visible through flowing water (flow of time, stream of consciousness); or similar objects in still water. A moment captured in time. The still is from a scene shot in sepia in a movie that has black and white footage though most of it is in colour. Andrei Rublev is in beautiful black and white with the final scenes in colour.

The religious image in the pool segues with the religious iconography from Andrei Rublev: the films deal with the corruption of man and religion through venality, lack of faith; the resurgence of spirituality via hope and redemption. The decline of society and mores is a resonant theme in Metropolis and Megalopolis. Additionally, Solaris and Stalker are also deeply philosophical films.

[4] Which also helps explain why Coppola compared his film to Joyce’s notoriously difficult book. The last line of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake ends in mid-sentence and leads back to the opening lines of the novel as it is meant to be a loop, like the Ouroboros: the serpent that consumes its own tail and so itself; a symbol of cyclical life; the wheel of existence keeps turning; immortality. A work meant to exists in a space-time of its own, eternally.

[Top picture: Cannes Film Festival; featured picture: Metropolis (1927), Kilian Eng.]

The writer is the founding editor of Philosophers for Change.

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change, philosophersforchange.org. Thanks for your support.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International.