by Zoltan Zigedy

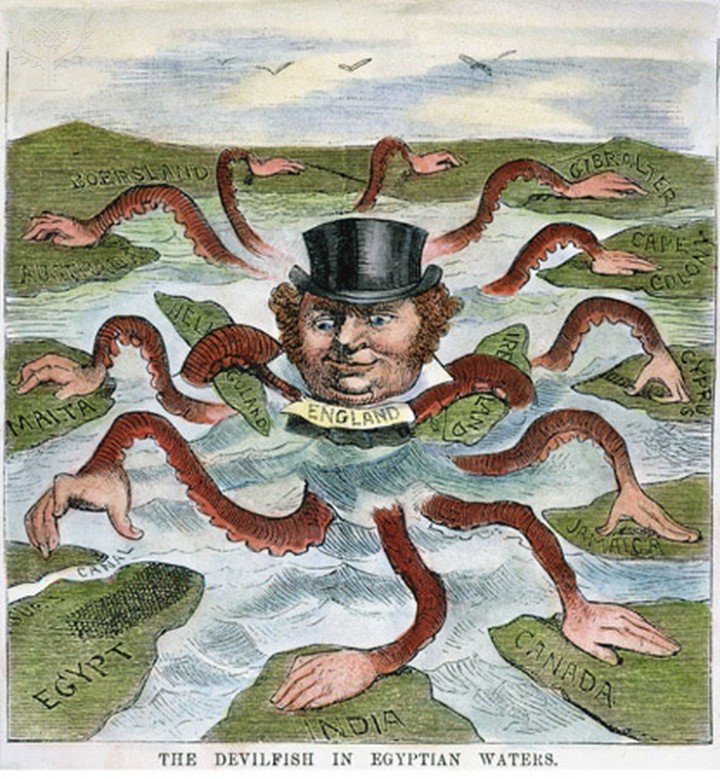

Imperialism, expressed as a nation’s securing economic dominance of, influence over, or advantage from other nations, remains much as Lenin characterized it in his 1916 pamphlet, Imperialism. Its uninterrupted persistence, from the time well before the pamphlet’s publication through today, certainly supports the claim that it constitutes the “highest stage of capitalism.” Its basic features, as outlined by Lenin, remain the same over a century: monopoly capital serves as its economic base, it supports a profound and growing role for finance capital, and the exportation of capital to foreign lands continues as a primary aim. Corporations spread their tentacles to every inhabitable area of the world and nation-states vie to encase those areas in their protected spheres of influence. War is the constant companion to imperialism.

While the character and grand strategy of imperialism never changed, the tactics evolved and shifted to adjust to a changing world. New developments, shifting power relations, and new antagonisms produced different responses, different approaches toward the imperialist project. With the success of the Bolshevik revolution in the immediate wake of an unprecedented bloodletting for nakedly imperial goals, the task of suffocating real existing socialism rose as the primary focus of imperialist powers. Those same powers recognized that the Soviets were encouraging and aiding the fight not only against the spread of colonies, but against their very existence.

Consequently, it is understandable that the next round of imperialist war was instigated by rabidly anti-Communist, extreme nationalist regimes in Germany, Italy, Spain and Japan. World War II came as a caustic mix of expansionism, xenophobia, and anti-Communism.

In the twentieth century, accelerated by the technologies of war honed in World War I, oil production played a greater and greater role in shaping the future fields of imperial contest. Acquiring oil and other resources was not an insignificant factor in the aggressions of both Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Clearly, both economic factors and political factors shaped the trajectory of imperialism in the first half of the twentieth century.

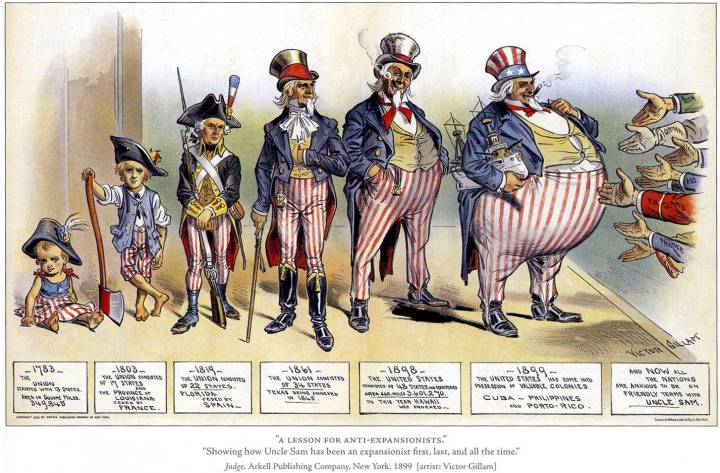

While no one doubts that the old European great powers hewed to an imperialist course until World War II (after all, they ferociously clung to their colonies), the myth still exists that the US was a reluctant imperialist. Apologists point to the ‘meager’ colonial empire wrenched from Spain (conveniently ignoring the nineteenth-century expansion from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans as well as the deals, wars, and genocide that ‘earned’ that expansion). They point to the ‘isolationist’ foreign policy of the US following the Treaty of Versailles, a claim demolished by the historian William Appleman Williams and his intellectual off-spring.[1] Appleman Williams showed that imperialist ends are achievable by many means, both crude and belligerent and subtle and persuasive. He showed that domination is effectively achieved through economic ties that bind countries through economic coercion, a tactic as effective as colonial rule. US policy, in this period, anticipates the financial imperialism of the twenty-first century. Appleman Williams and others revealed a continuous US imperialist foreign policy as doggedly determined as its European and Asian rivals.

A new model prevails

After World War II, the balance of power shifted in favor of a Euro-Asian socialist bloc centered around the Soviet Union and a liberated China, threatening even greater resistance to imperial world dominance. Through both mass resistance and armed struggle, colonial chains were loosened or broken. The war-weakened European powers strained to hang on to their colonial possessions. Moreover, the US, the supreme capitalist power, largely rejected the old colonial model.

In its stead, less coercive, but even more binding economic ties were secured through ‘aid,’ loans, investments, and post-war institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. This ‘neo-colonial’ tactic especially recommended itself because of the needs of the Cold War and the vast economic asymmetries favoring US power. Since the Cold War was also a monumental battle of ideas, US rulers sought to cast aside the ugly, oppressive imagery of colonial administration and military occupation. Further, the enormous need for capital by those under-developed by colonialism or ravaged by war could easily be fulfilled by the US, but at the price of rigid economic ties binding a country to the global capitalist economy now dominated by US capital.

The towering figure of Africa’s most fervent advocate for unity, socialism, and defiance of imperialism, Kwame Nkrumah, was a pioneer in developing our understanding of neo-colonialism. He wrote in 1965 in words that ring true today:

Faced with the militant peoples of the ex-colonial territories in Asia, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, imperialism simply switches tactics. Without a qualm it dispenses with its flags, and even with certain of its more hated expatriate officials. This means, so it claims, that it is ‘giving’ independence to its former subjects, to be followed by ‘aid’ for their development. Under cover of such phrases, however, it devises innumerable ways to accomplish objectives formerly achieved by naked colonialism. It is this sum total of these modern attempts to perpetuate colonialism while at the same time talking about ‘freedom,’ which has come to be known as neo-colonialism.[2]

President Truman affirmed the US commitment to the evolved neo-colonial program in his 1949 inaugural address when he rejected the ‘old imperialism.’

Gordon Gray, in a special report to the President issued on November 10, 1950, offered a motivation for the new program:

The largest part of the non-Soviet world… measured in terms of population and land areas, consists of economically underdeveloped regions. With some exceptions, the countries of the three areas–Latin America, Asia, and Africa–fall into this category. In the non-Communist parts of these areas live… 70 percent of the population of the entire non-Soviet world. These areas also contain a large part of the world’s natural resources… [T]hey represent an economic potential of great importance… The contrast between their aspirations and their present state of unrelieved poverty makes them susceptible to domestic unrest and provides fertile ground for the growth of Communist movements…[3]

But the US variant of classical imperialism predates the Cold War instantiation embraced by the Truman administration. As Appleman Williams notes, post-World War I leaders like Hoover, Coolidge, Hughes, and Stimson endorsed an international ‘community of interest,’ achieved by encouraging the penetration of US business worldwide. In Appleman Williams’s words, “These men were not imperialist in the traditional sense… They sought instead the ‘internationalization of business’… Through the use of economic power they wanted to establish a common bond… Their deployment of America’s material strength is unquestioned.”[4]

It is important to note that their choice of a more benign imperialism was not based upon moral considerations, but self-interest. Moreover, it necessarily preferred stability when possible, even if stability came through the exercise of military might. President Coolidge acknowledged this in a Memorial Day address in 1928: “Our investments and trade relations are such that it is almost impossible to conceive of any conflict anywhere on earth which would not affect us injuriously.”[5] As a late-comer to the imperial scramble, US elites chose the non-colonial option, avoiding the enormous costs in coercion, counter-insurgency, and paternalistic occupation associated with colonialism–and equally avoiding conflicts that might rock existing and expanding business relations.

In the post-World War II era, the Marshall Plan and The Point Four program were early examples of neo-colonial Trojan Horses, programs aimed at cementing exploitative capitalist relations while posturing as generosity and assistance. They, and other programs, were successful efforts to weave consent, seduction, and extortion into a robust foreign policy securing the goals of imperialism without the moral revulsion of colonial repression and the cost of vast colonies.

In the wake of World War II, US imperialism reaped generous harvests from the ‘new’ imperialism. Commerce Department figures show total earnings on US investments abroad nearly doubling from 1946 through 1950. As of 1950, 69% of US direct investments abroad were in extractive industries, much of that in oil production (direct investment income from petroleum grew by 350% in the five-year period).[6] Clearly the US had recognized its enormous thirst for oil to both fuel economic growth and power the military machine necessary to protect and enforce the ‘internationalization of business.’

One estimate of the rate of return on US direct investments from 1946 to and including 1950 claims that Middle Eastern investments (mainly oil) garnered twice the rate of return of investments in Marshall Plan participant countries which, in turn, produced a rate of return nearly twice that of investments made in countries that did not participate in the US plan.[7] Undoubtedly, US elites were pleased with the rewards of the new imperial gambit.

Patterns were set in the period immediately after World War II, patterns that persist even today. The basis for US hostility toward Venezuela can be anticipated in US imperialism’s early stranglehold on the Venezuelan economy. As early as 1947, the US exported nearly $178 million of machinery and vehicles to that country, primarily to and for foreign-owned oil companies. Only $21 million of that total went to domestically owned companies or for local agricultural use. In the same year, the income from American direct investments totaled $153 million.[8] Is it any wonder that the US would meet any independent path of development, such as the Bolivarian Revolution, with intense resistance?

The idea of parlaying economic power, capital resources, loans, and ‘aid’ into neo-colonial dependency through the mechanisms of free and unfettered trade–the ‘internationalization of business’–may well be seen as the precursor of the various trade organizations and trade agreements of today, like GATT, NAFTA, TPP, and so many other instruments for greasing the rails for US corporations.

Outside of the socialist bloc, much of the world was newly liberated from colonial domination, but ripe for imperialist penetration in the post-war era. For two decades after WWII, the socialist bloc was united in solidarity with the forces in opposition to imperialism. Arrayed against the anti-imperialist alliance were the imperialist powers bound together by the NATO alliance and their client states. In the imperialist camp, the anti-Communist Cold War imperatives secured US leadership and contained inter-imperialist rivalries in this period.

Two worlds, or three?

It is both useful and accurate to characterize that era as a confrontation between imperialism and its opponents: imperialism and anti-imperialism.

But in the battle of ideas, Western intellectuals preferred to divide the world in a different fashion. They preferred to speak and write about three worlds: a First World of developed, ‘advanced’ capitalist countries, a Second World of Communism, and a Third World of underdeveloped or developing countries. Clearly, the gambit here was to isolate the world of Communism from the dynamics of global capitalism and plant the notion that, with the help of some stern advice and perhaps a loan, the Third World could enjoy the bounty of the First World. The Three-World concept captured completely the world view espoused by Gordon Gray in his missive to President Truman quoted above. Assuredly, the three-world distinction was both useful and productive for elites in the West–decidedly more useful than the division between imperialists and anti-imperialists.

Sadly, late-Maoism, breaking away from the socialist bloc, uncritically adopted the three-world concept in its polemics against the Soviet Union. Embracing a tortured, twisted re-interpretation, Maoism sought to separate the socialist world from the anti-imperialist struggle and establish the People’s Republic of China as a beacon for the Third World. In reality, this theoretical contortion resulted in the PRC consistently siding with imperialism for the next three decades on nearly every front, including and especially in Angola and Afghanistan.

Unfortunately, significant sectors of the Western left fell prey to the confusions engendered by the debates of that time. To this day, many liberals and left activists cannot locate opposition to US dominance as objectively anti-imperialist. They place their own personal distaste for regimes like that of Milosevic, Assad or Gaddafi ahead of a people’s objective resistance to the dictations of imperialism. Confusion over the central role of the imperialism/anti-imperialism dynamic breeds cynicism and misplaced allegiances.

For example, Islamic fundamentalist fighters sided with imperialism against the socialist-oriented government of Afghanistan and Soviet internationalists. When the same forces turned on their imperialist masters their actions, not their ideology, became objectively speaking anti-imperialist. For other reasons–irrationalism, fanaticism, intolerance–we may condemn or disown them, while locating them, at the same time, in the framework of anti-imperialism. Similarly, in the imperialist dismantling of Yugoslavia, it doesn’t matter whether imperialism’s collaborators were Croatian Ustashi-fascists, or Bosnian liberals, they were all aligned with imperialism and its goals. Those who opposed these goals were acting objectively in the service of anti-imperialism. Moral rigidity is no excuse for ignoring the course of historical processes. Nor are murky notions of human rights.

As it has for well over a century, viewing international relations through the lens of imperialism/anti-imperialism serves as the best guide to clarity and understanding; imperialists prey as well upon those who we may find otherwise objectionable.

Confront or undermine?

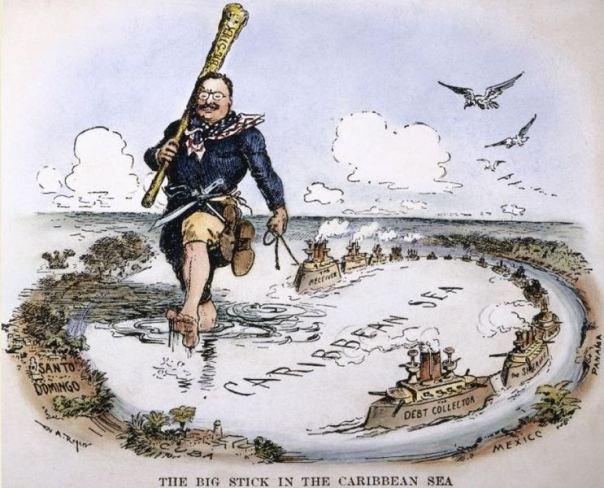

It would be wrong to leave the impression that US imperialism is solely based upon dollar persuasion or economic coercion. American military might exists as the international police force for imperial maintenance and expansion. The difference is that the US variant of imperialism chooses the option of planting military installations throughout the world–like the cavalry outposts of Western lore–rather than incur the costs of infrastructure and administration associated with Old World colonialism.

In addition, US imperialism confers special status on trusted watchdogs strategically placed in various regions. Before the revolution, the Shah’s Iran functioned as a regional cop, armed with the latest US weaponry. South Korea filled a similar role in the Far East, replacing Taiwan after US rapprochement with the PRC. With sensitivity to oil politics, the US has paired reliable Arab countries–Saudi Arabia or Egypt–with Israel to look after things in the Near East.

But employing regional gendarmes has challenged US policies as domestic upheavals or peer embarrassment has convinced some trusted clients that subservience will be widely viewed as–well, slavish subservience. Consequently, cooperation with the US has become more covert, less servile.

The hottest moments of the Cold War demonstrated that military confrontation with Communist led forces was not a wise move either in desired results or costs. The Korean and Indochinese Wars, interventions visiting a military reign of terror on small countries, proved that even the greatest imperialist military machine could not match the tenacity and dedication to victory of a far less materially advantaged foe. After the decisive victory of the Vietnamese liberators, the US never again sought a direct military confrontation with Communism.

But when the struggle of those fighting to escape imperialism and the capitalist orbit escalated, the US began relying more on surrogates, mercenaries, and clients. In place of direct military intervention, US policymakers relied on covert schemes, secret armies, and economic sabotage. In the Portuguese African colonies and South Africa, in Ethiopia, South Yemen, Nicaragua, Afghanistan and several other countries, Marxism-Leninism served as a guiding ideology for liberation and nation-building. At the same time, Marxist parties played a significant role in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), in the Portuguese revolution, and in European politics. By the end of the 1970s, the zenith of militant anti-imperialism and the global influence of Marxism-Leninism were reached. Imperialism appeared to be in retreat worldwide. And the leading imperialist country, the US, had suffered a domestic crisis of legitimacy from the extra-legalities of the Nixon Administration and serious economic instability.

Unfortunately, supporting this shift in the balance of forces globally came at great costs to the Soviet economy. The newly born, socialist-oriented countries were largely resource-poor, economically ravaged, and riven with ethnic and social schisms, all of which were easily and readily exploited by imperialism. Aid and assistance taxed the Soviet economy and in no small way contributed to the demise of the Soviet Union a decade later. Civil war, dysfunctional economies (thanks to colonialism), insufficient cadres, and unskilled administrators left those committed to building socialism facing a profound challenge, a challenge that proved impossible for most after the demise of the Soviet Union. It would have taken decades to integrate these countries into the socialist economic community. Unfortunately, they were not granted that opportunity.

Faced with a deteriorating international position, the cornerstone of the imperialist alliance–the US and the UK–changed course, electing regimes that refused to accept a restructured world order disadvantaging imperialism. The Thatcher and Reagan administrations signaled a new belligerence, a vigorous and aggressive assault on the twentieth-century bastion of anti-imperialism, the socialist community. A massive arms build-up and innumerable covert interventions coincided with the rise of an ideologically soft-headed Soviet leadership to dismantle the European socialist community in the decade to follow.

With the demise of the European socialist bloc, imperialism regained its nineteenth-century swagger, enjoying a nearly unopposed freedom of action. TINA–the doctrine that There Is No Alternative–seemed to prevail as much for imperial domination, as for capitalism.

A shaken international left faced a new, unfavorable balance of forces going into a new century. Far too many stumbled, took to navel-gazing, or spun fanciful, speculative explanations of the new era. The moment was reminiscent of the period after the failed revolution of 1905 famously described by Lenin:

Depression, demoralisation, splits, discord, defection, and pornography took the place of politics. There was an ever greater drift towards philosophical idealism; mysticism became the garb of counter-revolutionary sentiments. At the same time, however, it was this great defeat that taught the revolutionary parties and the revolutionary class a real and very useful lesson, a lesson in historical dialectics, a lesson in an understanding of the political struggle, and in the art and science of waging that struggle. It is at moments of need that one learns who one’s friends are. Defeated armies learn their lesson.[9]

Unfortunately, most of the left learned nothing from the defeat of 1991.

Militant anti-imperialism returns

If Marx teaches us nothing else, he reminds us that historical processes play out in unexpected, perhaps even unwelcome ways. The suppression of secularism as a tactic for disarming movements for independence or social progress is as old as the British Empire and probably older. Certainly the British colonial authorities were masters at divide and conquer, encouraging ethnic or religious differences to smother otherwise secular movements. It was this proven approach that joined US and Israeli policy planners in making every effort to discredit, thwart, split, and penetrate every secular movement in the Middle East: influential and substantial Communist Parties, left Ba’athists, radical democrats, nationalists, etc. The secular PLO was notably targeted. At the same time, they sought to use Islamic fundamentalists by covertly supporting them as an alternative and actively encouraging divisive conflict. Hamas was one such organization, chosen specifically as a hostile option to the militantly anti-imperialist PLO.

Similarly, the US and its allies sought to weaken the Soviet effort in Afghanistan by funding and arming the Islamic fundamentalists engaged in a civil war against forces advocating free, secular education, land reform, gender equality, and modernization.

Radical Islamic fundamentalism had waned in the 1950s and 1960s, losing momentum to the awakening inspired by Nasserism and other nascent national movements. But the encouragement and material support of the US and Israel rekindled these movements. Add the demise of the Soviet Union and the loss of support for secular national movements, and imperialism blazed a path for the growth and prominence of fundamentalism.

Not surprisingly, the grievances, the injustices endured by the people of the Middle East now found expression through the organs and institutions of fundamentalism, just as the peoples of Latin America found expression for their plight through the Catholic Church when denied other options by fascistic military dictatorships.

The Palestinian Hamas-inspired intifada shocked Israel and its allies from their smug arrogance. And the brutal attacks on US interests, the US military, and on targets in the domestic US further shocked imperialism. Lost in the revenge hysteria, hyper-patriotism, and religious bigotry fueled by the attacks were the casus belli invoked by the fundamentalists: the occupation of Palestine since the 1967 war and the use of Saudi bases as US military staging points before and after the 1991 invasion of Iraq.

While the targeting of civilians is regrettable, it is regrettable in its entirety: whether they be German civilians bombed by the allies in Dresden, Korean women and children massacred by US soldiers in Taejon, or villages destroyed by US aircraft in Vietnam. But it is more than a curiosity or a mark of barbarism that oppressed peoples facing a modern, advanced army with superior resources fight by different rules. Nor has there ever been an anti-imperialist movement that was not called ‘terrorist’ by its adversaries. Granting that Marx and Engels were not always consistent or correct on these questions, Engels offers insight in his column in the New York Daily Tribune published on June 5, 1857:

The piratical policy of the British Government has caused the universal outbreak of all Chinese against all foreigners, and marked it as a war of extermination.

What is an army to do against a people resorting to such means of warfare?… Civilization-mongers who throw hot shells on a defenseless city and add rape to murder, may call the system cowardly, barbarous, atrocious; but what matters to the Chinese if it be only successful? Since the British treat them as barbarians, they cannot deny to them the full benefit of their barbarism. If their kidnappings, surprises, midnight massacres are what we call cowardly, the civilization-mongers should not forget that according to their own showing they could not stand against European means of destruction with their ordinary means of warfare.

In short, instead of moralizing on the horrible atrocities of the Chinese, as the chivalrous English press does, we had better recognize that this is a war pro aris et focis, a popular war for the maintenance of Chinese nationality, with all its overbearing prejudice, stupidity, learned ignorance and pedantic barbarism if you like, but yet a popular war. And in a popular war the means used by the insurgent nation cannot be measured by the commonly recognized rules of regular warfare, nor by any other abstract standard, but by the degree of civilization only attained by that insurgent nation.[10]

Writing well over a century-and-a-half ago, Engels better understood the dynamics of anti-imperialist resistance than modern-day commentators, including most of the left.

Failing to understand the dynamic of ‘popular war,’ as Engels called it, only led to escalation: an invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, a subsequent invasion and occupation of Iraq, incursions in Somalia, drone attacks throughout the region, aggression against Libya, destabilizing Syria, isolating Iran and other actions proclaimed as ‘anti-terrorist,’ but perceived by the people of the Middle East as aimed at forcing their submission to outside diktats. Accordingly, there is little chance that the hostilities invited and unleashed by imperialism will ebb any time soon. Only an exit and a cessation of meddling can promise that result.

Writing in 1989, well before the full unfolding of militant Islamic fundamentalism, Manfred Bienefeld reflected upon what he saw as the dimming prospects for anti-imperialist struggle, speculating on the—

…terrible possibility that in today’s world these forces may be permanently beaten back aided by the massive resources and powers available to the ‘international system’ and their local collaborators. It is striking that those movements that appear to be capable of sustaining such resistance for any length of time are movements like those of Islamic fundamentalism which refuse to calculate costs and benefits according to the calculus of those who shape the international system. [my emphasis][11]

Bienefeld’s words were eerily prescient.

Like the Chinese response to British aggression, the resistance to US imperialism in the Middle East has been nasty; fighters have refused to submit to incineration and slaughter like the Iraqi army when faced with an overwhelmingly overpowering conventional army in 1991 and 2003. And like the English press cited by Engels, the Western media moralizes over tactics while purposefully ignoring the century of great-power aggression, occupation, and colonization of the region. For the apologists of imperialism, the systematic injustices of the past carry no moral weight against the most desperate actions of the powerless. One is reminded of the scene in Pontecorvo’s brilliant film, The Battle of Algiers, when the captured Ben M’Hidi is asked by a reporter why the liberation movement, FLN, plants bombs in discos and schools. His reply is succinct: “Let us have your bombers and you can have our women’s baskets.”

Where Islamic fundamentalism will take the people of the Middle East (and other areas of largely Islamic populations) is unclear. Close study of the different threads would undoubtedly show different and socially and economically diverse prospects. But what is clear is that as long as it carries the mantle of the only force resisting imperialism in the region, it will enjoy support and probably grow, though fraught with the contradictions that come from religious zealotry.

Risings in the south

Resistance to imperialism in the backyard of the US–Central and South America–has a long and noble history: long, because it traces back to the fight of the indigenous people against conquest and enslavement; noble, because millions have given life and limb in wars of liberation and movements of resistance.

But it wasn’t until 1959 that a Latin American country broke completely away from the grasp of imperialism. The Cuban revolution produced a government hostile to foreign intervention, rapacious landowners, and greedy corporations—a formula sure to bring the disapproval of the powerful neighbor to the north. The rebel leaders met threats with defiance. As US belligerence began to suffocate the revolution, the Cuban leaders turned to and received support from the socialist community. In retaliation for this audacious move, the US organized an invasion of the island, only to be met with overwhelming, unexpected resistance. Unable to bring Cuba to its knees, imperialism enacted a cruel quarantine of Cuban socialism that persists to this day.

In the post-war era, the cause of the Popular Unity program in Chile inspired a generation in much the way that the cause of the Spanish Republic inspired a generation in the 1930s. The Allende government embodied the aspirations of nearly the entire left: a break from US imperial domination and a peaceful, electoral road to socialism. In 1973 those aspirations were dashed by economic subversion, the CIA, and a brutal coup launched by the Chilean military. More importantly, the coup in Chile sent the message that US imperialism would readily accept military, even fascist rule in Latin America before it would tolerate others following the Cuban path, the path away from imperialist domination.

But the tide of anti-imperialism could not be held back. Leaders like Lula, Rousseff, and Bachelet emerged from resistance to military dictators or, like Morales, from trade union militancy. As democratic changes inevitably surfaced, all were positioned and prepared to take their respective countries in another direction. The Kirchners in Argentina were more a product of the Peronista tradition of populist nationalism, a tradition often annoying the superpower to the north.

But most interesting and, in many ways, most promising, was the emergence of Hugo Chavez as the lightning rod for anti-imperialism in Latin America. Because Chavez rose from the military, he seemed to hold a key to unlocking the problem of military meddling in Latin American politics. Moreover, the Venezuelan military was a Latin American rarity–a military unwelcoming to US training and penetration. Chavez’s prestige with the military held or neutralized much of the military from going over to the 2002 coup attempt.

Clearly the most radical of the wave of new Latin American leaders, Chavez advocated for socialism. While Venezuelan ‘socialism’ remains a visionary, moralistic project, neither fully developed nor firmly grounded, it counts as an energetic pole raising questions of economic justice in the most profound fashion. Growing from a strong personal relationship between Hugo and his spiritual kin, Fidel, Cuba and Venezuela mark one pole of militant anti-imperialism. Together, they stand for political and economic independence from the discipline of great powers, their institutions, and transnational corporations.

Because they cherish their independence, they have earned the enmity of US imperialism. Lest anyone believe the recent trade for the Cuban patriots negotiated by the Cuban government means that the US government seeks peaceful co-existence with anti-imperialism, think again. The US has, in fact, escalated its aggression against Venezuela and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea on the heels of that exchange.

The other social and political movements formed in Latin America range across the political spectrum from cautiously social democratic to avowedly socialist. They stretch from Nicaragua in Central America through the entire Southern continent. Though they have no common political ideology, they have a shared aversion to accepting the demands of greater powers, a refusal to toe the imperialist line. To a lesser or greater extent, they support independence from the economic institutions governing the global economy. And they tend to support the consolidation and mutual support of their vital interests within the Latin American community. To that extent, they constitute a progressive, anti-imperialist bloc.

Today’s imperialism and its problems

Any survey of imperialism and its adversaries must note the pathetic role of most of the US and European left in recent years. Even in the most repressive moments of the Cold War, large anti-war movements challenged militarism, aggression, and war. But those movements have shriveled before indifference and ideological confusion. In the post-Soviet era, imperialism cynically appropriated the language of human rights and manipulated or bred an entire generation of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with innocuous, seemingly socially conscious banners, but disruptive missions. So-called ‘color’ revolutions proliferated, paradoxically supported and directed by a host of government and private-capital funded NGOs. These organizations promoted a brand of ‘democracy’ that mobilized Western-oriented liberals and Western culture-mesmerized youth against established, often election-legitimized governments. Most of the Western left naively applauded and uncritically supported these actions with no understanding of the forces at play.

Much of the European and US left passively watched the dismantling of Yugoslavia–blinded by NATO proclamations about self-determination and ethnic violence, as if kindling the fires of extreme nationalism would produce anything other than separatism and hatred. In a masterful assault on credibility, NATO bombs were interpreted as enforcing human rights in Serbia and Kosovo.

The imperialist game of deception proved to work so well that it has been repeated again and again, in Iraq, Libya, Ukraine, and Syria, to only name a few. It’s a sad commentary on the US labor movement (and its European counterparts) that it stands aloof from US imperialism (when not assisting it). Samuel Gompers, the conservative, first President of the American Federation of Labor joined the Anti-Imperialist League over a century ago; his counterparts of today cannot utter the words.

Looking back, it is likely that few if any of the US and NATO aggressions of the last twenty-five years would have been dared if the Soviet Union still existed. Put another way, nearly all of the many interventions and wars against minor military powers were initiated because the US recognized that there was no powerful deterrent like the former Soviet Union. In that sense, imperialism has had a free hand.

Nonetheless, while twenty-first century imperialism endures, it does so despite great challenges and severe strains. Unending wars and deep and lasting economic crises have winded the US and its NATO allies. Military resistance to imperialism has proven resilient and determined, as would be expected of those fighting in defense of their own territory. The US all-volunteer military and low casualty rate have been a calculated success in pacifying many in the US, yet there is a widespread disillusionment with war’s duration and lack of resolution. Despite media courtiers continually stirring the pot of fear and hatred with hysterical calls for a war on ‘terror,’ the cost of that war in material and human terms becomes more and more apparent.

Memories of Vietnam haunt military strategists in the US who are finding it difficult to disengage in the face of escalating violence and the surfacing of new adversaries. It may be tempting to follow the lead of many liberals and label the trail of broken nations, shattered cities, slaughtered and maimed people traveled by the US military, its mercenaries, and camp followers as a product of incompetence and miscalculations. It is not. Instead, it is the product of imperialism’s failure to peacefully maintain a global economic system that guarantees the exploitative and unequal relations that enable imperialist dominance. In fact, it is a sign of a weakening imperialism that less than thirty years ago triumphantly stood admiring its final victory.[12]

The old symptoms return to afflict imperialism. Lenin saw the intensification of imperialist rivalries–competition for resources, spheres of influence, capital penetration–as an intrinsic feature of imperialism. In his time, the British Empire dominated, but with Euro-Asian rivals rising to challenge its supremacy. Commentators noted the ‘scramble’ for colonies and the rising tensions that ensued. Military and economic blocs were formed to strengthen the hands of the various contestants. World War followed.

While inter-imperialist war may not be imminent, the signs of discord, intensified competition, and shifting alliances are growing. Tensions between the US, the People’s Republic of China, Russia, and even the EU are constant. Japanese nationalism has stirred historic antagonisms in the Pacific region, challenging the PRC’s economic might. The US has sought not to diffuse these tensions, but to intervene to advance its own interests.

The US has promoted or prodded Eastern European nationalism to shear away countries that were formerly accepted as part of the Russian sphere of influence. Not surprisingly, Russia has interpreted these moves as hostile acts and taken countermeasures. The Ukrainian crisis has produced belligerence unseen since the Cold War. At the same time, the EU opposes escalating anti-Russian punitive sanctions urged by the US, sensing the danger of disrupted economic relations and even war at a time when the European community is already suffering severe economic pain.

New alliances have formed as a counter force to US imperialism. The BRIC group, for example, exists as a loose community made up of significant players in the global capitalist economy: PRC, India, Russia, and Brazil. Though the members are not ostensibly in conflict with the US, they oppose the hegemony of the US in international institutions and the tyranny of the US dollar in international markets. They espouse a multi-polar world without US domination. Theirs is not an anti-imperialist bloc, but an anti-US hegemony bloc. They are not opposed to the predation inherent in international economic competition; they are only opposed to US dominance of that predation.

This is in contrast to the ALBA bloc, a group of eleven Caribbean, Central and Southern American nations establishing an economic community. ALBA was envisioned by then Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez as an alliance moving to escape the clutches of the global economic system. Chavez saw the expanding development of mutual trade, shared institutions, integration and a common currency as steps toward a community more and more removed from the rapacious international capitalist system. Of course that is a promise only to be realized far into the future. Moreover, it is a project only capable of achieving escape velocity when the member states embrace socialist economic principles. Nonetheless, ALBA counts as a significant irritant to imperialism.

Political forces are unleashed worldwide that promise to disrupt the course of imperialism. Unanswered economic discontent has fueled nationalism and religious zealotry, forces that inspire distrust of existing institutions and open markets. Spain, for example, is riven with separatism; even the UK is threatened with Scottish autonomy. Economic nihilism and conspiratorial xenophobia have strengthened neo-fascist movements throughout Europe to the point where they seriously threaten the existing order.

Clearly, the political, social, and economic fabric of imperialism, its stability, and its ability to govern the world is under great stress. From world economic crisis to interminable wars, the world system has fallen far from its moment of celebration at the end of the Cold War.

Indeed, imperialism has changed. Colonialism–with the exception of Puerto Rico, Guam and a few other remnants of the past–is gone, with vestiges, like Hong Kong, either absorbed or liberated. Yet what otherwise exists today strongly resembles the imperialism of Lenin’s time, the imperialism of economically vulturous nations unfettered by a counter force like the Soviet Union. Perhaps, the ‘new’ imperialism is little more than a return to the imperialism that opened the last century with the US replacing Great Britain as the dominant imperial power–the ‘new’ is simply the reassertion of the old.

Understanding today’s imperialism requires some ideological re-tooling. The days of an alliance of socialist countries and newly liberated colonies searching for new roads under the socialist umbrella are past. In its stead are capitalist countries competing against the more dominating capitalist countries. Should they succeed in deposing the US, they in turn will fight to retain hegemony. That is, they will behave like a capitalist country. Of course opposing US hegemony is objectively anti-imperialist even when it seeks to impose its will on another capitalist country (Russia, today, for example). Indeed that is part of the struggle against imperialism–an essential part. Likewise, the struggle to resist and end US aggression and occupation of lands in the Middle East is a component of the contest with imperialism.

But the fight to end imperialism once and for all is the fight to end capitalism.

[Graphic: The Guardian]

End notes:

[1] See The Legend of Isolationism in the 1920’s, Science and Society, Winter, 1954 for an early exposition of this thesis.

[2] http://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/nkrumah/neo-colonialism/ch01.htm

[3] The Point Four Program: Promise or Menace? Herman Olden and Paul Phillips, Science and Society, Summer, 1952, p 224.

[4] The Legend of Isolationism in the 1920’s, Science and Society, Winter, 1954, pp 13-16.

[5] Ibid. p 16.

[6] All data from Olden and Phillips pp 234-237.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Olden and Phillips, p 232.

[9] Lenin, ‘Left-Wing’ Communism, an Infantile Disorder, International Publishers, 1969, p 13.

[10] Engels, Friedrich. Persia and China, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels on Colonialism, Foreign Languages Publishing House, ND, pp 127, 128.

[11] Bienefeld, Manfred. Lessons of History and the Developing World, Monthly Review, July-August, 1989, p 37.

[12] Most famously, in Francis Fukuyama’s triumphalist The End of History and the Last Man, 1992.

[Thank you ZZ for this essay.]

Zoltan Zigedy is the nom de plume of a US based activist in the Communist movement who left the academic world many years ago with an uncompleted PhD thesis in Philosophy. He writes regularly at ZZ’s blog, and on Marxist-Leninism Today. His writings have been published in Cuba, Greece, Italy, Canada, UK, Argentina, and Ukraine.

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change, philosophersforchange.org. Thanks for your support.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Reblogged this on ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ.