by Angelo J. Letizia

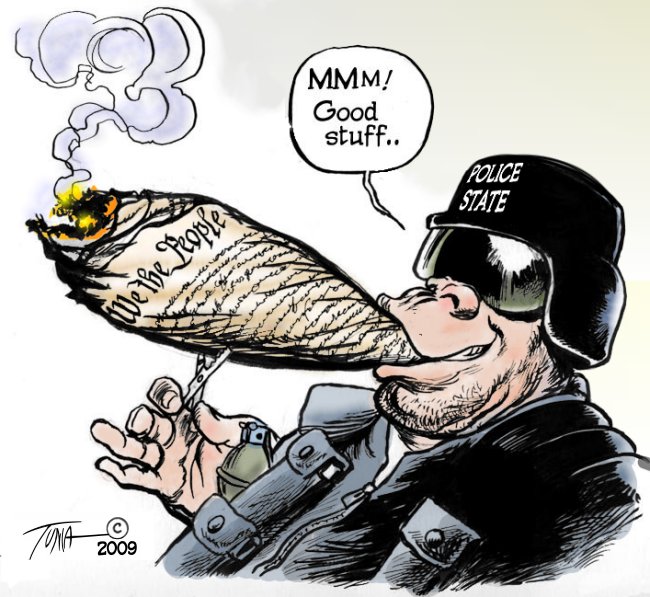

In a recent article, Dr. Henry Giroux argued that we may be witnessing the dismantling of democracy (Giroux, 2013). He pointed to the neoliberal assault on public education and the transformation of public education into workforce training for the global economy at the hands of state and federal law makers (Giroux, 2013). Giroux’s remarks are sobering. They may actually be more telling than even he realized. Perhaps the neoliberal assault on education is not the destruction of democracy, but rather something much more profound; it may be the end of the Enlightenment.

While it is impossible to put exact definitive markers on historical events, historians argue that the Enlightenment began roughly at the end of the seventeenth century. Enlightenment thinkers such as Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Marquis Condorcet, Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Jefferson and later Georg Hegel all wrote of the power of a progressive and liberal education grounded in history and the liberal arts; they wrote about civic duty, public service and the infallibility of true democracy. While their thoughts are varied, and at times contradictory, they all demanded equality, freedom, justice, the rule of reason and the suppression of superstition. Their writings are imbued with a sense of optimism; those social problems such as hunger, poverty and war can and would be solved with human effort. Jefferson in particular wrote that an educated citizenry has to be the foundation of any true republican government. Further, he wrote citizens need to be taught history because only with a historical education could they truly hold their leaders accountable (Jefferson, 1962).

These powerful Enlightenment ideas animated the American and French Revolutions. Historians squabble about the date the Enlightenment ended; many argue that it came to an end after the French Revolution. Yet, the ideals of the Enlightenment never died. In many ways they helped to inspire democratic and socialist movements during the nineteenth century, the abolition of slavery, the progressive era, women’s suffrage, and the radical protests of the 1960s to name some of the more famous events. By the 1980s, Jürgen Habermas argued that we must continue to fight for the ideas of Enlightenment, that the ideas of freedom, justice, equality and the rights of the individual were things worth fighting for (Habermas, 1990). Giroux and others, such as Dave Hill, have argued for democratic pedagogy to help instill these Enlightenment values in students and help them carry them to the next generation (Giroux, 2011; Hill, 2012).

Yet, by the 1980s, neoliberals had begun their assault on public education and in a larger sense the values of the Enlightenment. Newfield argued that one of the main intents behind the assault on public education has been driven by a recognition by conservatives of the power of a liberal and progressive education. After the events that higher education helped to inspire in the 1960s, conservatives began an assault on public K-12 and higher education. The weapon they used was the market; they claim that public education is not efficient; it does not prepare students for the marketplace and workplace (Newfield, 2008). In 2013, Giroux’s statement that we may be witnessing the dismantling of democracy has become all the more prophetic. Yet it is not a reason to retreat into cynicism. Rather, it should be a call to arms. There is no magical force driving history. There is only human action. Educators must mobilize and fight for their students, for democracy and for the Enlightenment itself.

Many papers on this site argue for some type of historical movement. Many scholars see contemporary society undergoing revolutionary change (Hill, 2012). Some have noted that capitalism may be in its death throes, others have labeled it casino capitalism (Giroux, 2013) or corporate totalitarianism (Hedges, 2013). Hedges wrote of a silent revolution brewing amongst different facets of society which will eventually topple the ruling order (Hedges, 2013). There is little doubt that we do live in a historical age and that society is progressing. The above forecasts may indeed be occurring, or are close to occurring. At the same time however, the forces of the status quo are still strong and repressive. Their strength is not only physical, but mental. The ruling regimes police our minds and regulate the flow of information through the media, government and education. While forces of opposition may be brewing, the forces of repression are still dominant. With this in mind, the present analysis argues that the Enlightenment may be coming to an end with the assault on public education and critical thinking. If students no longer learn how to think critically, or how to judge their leaders and societal institutions, they can no longer participate in their democracy.

So, our age is revolutionary, the forces of historical motion are in full swing. Yet, what exactly does historical movement look like? We speak in high terms of social and historical progression, but now we must actually visualize and demonstrate it. If this is truly the end of the Enlightenment, and conversely if opposition forces are rising to meet this threat, what does this process look like? In the 19th century, Marx explicitly detailed what he saw as the death of the capitalist order. He argued that through dialectic motion, socialism and then finally communism would emerge. Capitalism brought forth its own gravediggers by enriching certain members of the bourgeoisie class and impoverishing the vast majority of them, creating ever more proletariats (Breckmen, 1999). While this is a simplified view of Marxism, it does speak to the notion that is central to Marx’s theories: that the very processes of capitalism worked to destroy capitalism. Once these legions of impoverished proletariats took hold of their situation, they would topple the remaining bourgeois and institute the dictatorship of the proletariat. While this has failed to happen exactly as Marx prophesized, it nonetheless does give us insights into the nature of capitalism.

However, as the critical theorists have made clear over the course of the 20th century, the situation regarding capitalism has drastically changed. We now live in the age of global capitalism. So, what does historical and social movement look like in this age of advanced capitalism? Where do changes occur and how do they occur? For this question, we must start with the individual. We need to dissect the many societal occurrences that impact an individual. Society is not a fiction as many neoliberals hold, but it does make sense to examine the smallest building block of society and progress outwards. Here, the developmental psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner’s work is useful to understand the different levels of social phenomena.

Bronfenbrenner’s work outlines different layers of an individual’s environment which impact the individuals’ development. Bronfenbrenner’s theory had four main components: process, person, context and time. It is the interaction of these different components that can promote or hinder development (Evans et. al, 2010). Processes are the actual interactions between the individual and the environment. Each individual has a certain set of characteristics which affects the way he or she interacts with the environment. Contexts are the actual environments and settings where actions take place. Bronfenbrenner saw the individual situated in a location and surrounded by four levels or systems. It was from his or her context where the processes, other contexts and individual characteristics interact.

The first level of Bronfenbrenner’s theories was the microsystem, which encompassed the day to day interactions of the individual, such as workplace, family structure, and friendship groups. The second level was the mesosystem. The mesosystem is made up of linkages between the various microsystems. The next level is the exosystem. The exosystem does not contain the individual, but nonetheless exerts an influence on the individual (Evans et. al, 2010). Examples of exosystems are federal and national policies. The last phase is the macrosystem, which comprises social and cultural trends (Evans et. al, 2010).

Many dialectical theories examine large swathes of history and time, cultural occurrences, historical events, social trends etc. In Bronfenbrenner’s terms, these theories remain in the macrosystem. These are the most profound changes in any given society because not only do they affect virtually all individuals, but changes in the macrosystem also involve pushing against entrenched norms. Yet, sometimes in this examination of the macrosystem, we lose sight of the individual and how individuals interact with each other and their environment. And it is these individual actions, relations with the environment, and overall processes that are the inner working of society and real dialectical change. Marx famously argued that men make history but not of their own will, rather, they were carried along by it (Breckmen, 1999). Marx privileged the economic functions of society as the prime motivators of human action and movement. The rest he considered “superstructure,” such as morality, laws and education, and are of little use in directing social movement and progression of history. This is not to suggest that Marx saw any “world spirits” or other supernatural forces guiding history. History was the work of human actions, but it was actions in the aggregate (Breckmen, 1999).

There is some truth in this. Economic factors, such as the (now) global economy, poverty, predatory lending, casino capitalism and corporate totalitarianism are prime movers of human action, and are at the base of the superstructure. The “morality” and norms of the global economy have been internalized by many in society and form the foundation of our government, law and ethics (Giroux, 2011; Hill, 2012). Yet, to deny human agency is also to deny human accountability and potential to rectify injustice. As Kincheloe has argued, modern critical theory and critical pedagogy in particular, while admitting the influence of economic functions, nonetheless recognize that elements of the superstructure can and do influence economic functions (Kincheloe, 2007). More than this, any occurrence in society is motivated by a complex bundle of economic, social, cultural, and psychological factors (Kincheloe, 2007). If we follow Kincheloe’s train of thought, then the different levels of Bronfenbrenner’s theory become useful. We cannot assume that all change happens at the macrosystem and is due mainly to economic functions. Rather, we can begin to dissect the workings of the exo-, meso- and right down to the microsystems of individuals. From here we can progress outward and try to build a web of interaction and ultimately a tenuous map of social change at all levels.

This piece began by declaring that we may be witnessing the end of the Enlightenment. Following Giroux, pedagogy must be at the center of any democratic polity (Giroux, 2011). Thus, an assault on public education is an assault on democracy, and in the widest sense, the true democratic government, a government for the people and by the people, is a creation of the Enlightenment. We have only spoken of it in the macrosystem, as a broad and sweeping change. As Giroux and others have noted, we see a shift in the attitudes toward education. While education always had economic uses, such as helping the individual secure a high paying job and being workforce trained, education — especially higher education — was always thought of as primarily a social good with the ability to enhance the commonweal (Newfield, 2008). Yet, over the last 40 years, this vision of education has shifted to a more market based view (Zumeta, 2011). Education is now primarily seen as a market good, solely as workforce training and the molding of good consumers (Giroux, 2011; Hill, 2012). But what does it look like in an individual’s day-to-day life? And how has this change been enacted and pursued? For this, we can turn to Bronfenbrenner’s model as a framework.

Change in the Exosystem

The Exosystem is composed of federal and state policies (in the United States), supranational policies such as policies of the UN, and more importantly other global organizations such as the World Bank and World Trade Organization. In addition to political bodies, the actions of corporations, nonprofit organizations and other entities also reside in the exosphere. As mentioned earlier, the individual has very little if any influence on the workings of the exosystem, and these occurrences are outside of the daily purview of the individual. Nonetheless, while distant, these workings exert great influence on the individual. In the case of education, the policies of state governments, as well as the federal government, are the primary tools to restructure K-12 and higher education from social to market goods. They are not alone, however. In many ways, the federal and state governments act as mouth pieces for other more powerful entities in the exosphere: right-wing think tanks (and increasingly left-wing think tanks who have adopted similar visions of education as a market good), world governance organizations (whose members are not elected) and, of course, corporations (Peet, 2009).

Standardized testing companies and educational technology companies, which have grown into billion dollar entities and do billions of dollars of world trade, have lobbied the US government and other governments across the world to hold education accountable. They claim teaching quality has declined, students are not prepared for the workforce, public education is failing. They have created a crisis — and the means to fix the crisis (Klein, 2007). The solution: standardized tests to accurately measure student learning and teacher efficiency and educational technology to enhance learning. Companies such a Pearson, Houghton-Milfflin and Harcourt Brace bend Congress’ ear. The greatest example of this was the passage of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ act in 2002. Not one teacher was consulted in the writing of that policy. Instead it was largely left to “educational experts” from right-wing think tanks, standardized testing companies’ representatives and others hostile to traditional education (Fowler, 2009).

Countless other policies which are supposed to hold educators at both K-12 and higher education accountable have been passed through state legislatures in the US. A notable example is performance based funding (Zumeta, 2011). Performance based funding sets up definable goals for higher education institutions to meet, such as graduation rates, graduation of STEM graduates, use of data etc (Zumeta, 2011). A portion of a university’s funding is tied to the meeting of these goals — if an institution does not meet the goals, they are penalized and do not get the portion of their funding. Currently 12 US states have performance based funding policies and four other states are in the process of implementing them. Yet they seem to be the wave of the future (Zumeta, 2011). Like ‘No Child Left Behind’ (NCLB), these accountability measures are written, passed and enforced with little to no input from faculty. Instead, they are creations of corporate lobbyists who argue that K-12 and higher education is in a state of crisis and they have the methods to fix it. And those methods are extremely profitable for them. Milton Friedman once remarked that public education in the US was a socialist island in a free-market sea. The “crisis” of public education is just a mask for an invasion of this island. Once the invasion is complete, the soldiers of the free-market will hoist their dollar sign flags.

More than just greed (which it is), there is an ideological element to performance based funding policies and NCLB. These policies espouse and promote a certain view of education. Education is cast as a tool of the global market. Nowhere in any of the policies is there a mention of social justice, citizenship or other goals necessary for a democracy. Rather, the only sort of morality or ethics is the global market. We are told that students must be prepared for the global market. There is an element of fear in these policies. Conservatives are afraid of the potential of public education at all levels to inspire social change (Giroux, 2011; Newfield, 2008). After the events of the 1960s, it became apparent what public education was capable of. It could challenge the status quo and push for social justice, and this frightens the hell out of those in power.

So the far reaching change in social trends and cultural values in the macrosystem are put into place by the actual policies enacted in the exosystem. More than simple economics, there is a strong element of fear and ideology. Education is the most powerful weapon mankind has ever devised. In the hands of radicals this weapon is used for social justice, in the hands of conservatives it is used a way to prop up the status quo.

Change in the Meso- and Microsystems

The passage of ‘No Child Left Behind’ (NCLB) occurred in 2002. Seniors who will graduate in May and June of 2014 were six years old when NCLB was passed. Similarly, future college graduates who will be impacted by performance based funding policies are children and teenagers today. The point is to illustrate that the workings of the exosystem are distant from the individual but nonetheless very powerful. Seniors graduating in May or June of 2014 have been subject to NCLB virtually their entire school careers. They have taken a barrage of standardized tests; tests which measure nothing (Janesick, 2007). These tests only serve to catalogue and classify students. Struggling students cannot pass the tests and honors students pass them with ease. Neither gain anything from the tests. Instead of preparing for citizenship, engaging with social issues and learning the true workings of American politics, students regurgitate predetermined answers to tests.

Giroux and many others have argued that pedagogy must be synonymous with democracy. Through the process of critical pedagogy, students are transformed into citizens who then can participate in their democracy, just as Jefferson intended. The Enlightenment is based on the notion of criticism and humanism, both of which are not valued in American public education.

In a much wider sense for K-12 education, multiple choice tests (and even many standardized essay questions) transmit the idea that there is a right answer, and that an authority figure has it. Students cram to remember all the “right answers” without ever learning how to question the answers and the authorities that supply them. And questioning authority is the foundation of democracy. Students’ day-to-day interactions, the activity at their various microlevels and the mesolevel does not involve questioning, interpreting or analyzing, rather it simply involves remembering. And remembering the dictates of others is a form of obedience. Students remember the dictates of the global market. Students look to teachers as possessing the “right answer” and the teacher becomes simply an information transmitter. The transmission of information becomes a one way street, from teacher to student. In addition, collaboration between students and students, and students and teacher, is discouraged and not rewarded. Instead, each student is a solitary island, classified according to their mark on an arbitrary test. They no longer see their classmates as fellow citizens, but just as other consumers (Giroux, 2011; Janesick, 2007). In addition, teachers no longer look at students as citizens, but as potential passes and failures.

The situation in higher education is no different. Institutions become obsessed with meeting their performance targets. As a result they compete with each other, they lower academic standards and eliminate programs that are seen as unproductive, such as history and literary classes. In Texas, North Carolina and Florida, the republican governors have all taken aim at the humanities (Kiley, 2013). They argue that these disciplines do not help students compete in the global economy, and further that these disciplines do not lead to high paying jobs. One particular college, Elizabeth City University, a historically black college is moving to do away with the disciplines of history, political science and literary studies (Kiley, 2013). One official remarked on the sad irony of a historically black college cutting its history program. The point is that history, literary criticism and politics are all fundamental facets of the Enlightenment. And as stressed earlier, the Enlightenment was a movement to free humanity from its bondage to superstition, tyranny and oppression (Habermas, 1990). However, it may be very likely that students in the future will not have the same access to classes which can teach them to think this way because those classes are not deemed “efficient.” Students who do not have history, political science, philosophy and literary criticism classes may never talk about the serious issues that face American society. Instead they may simply want to pursue a career and make money and say forget about social justice and society. K-12 students forced to compete with each other, and college students deprived of critical thinking opportunities may be the death of the Enlightenment in the micro- and mesosystems.

Wrapping it up

The death of the Enlightenment occurs in the macro-, exo-, meso- and microspheres yet we tend to analyze it only from the macrosystem. This is also a chicken and egg type question. Do changes in the macrosystem facilitate changes down to the individual, or do individual changes percolate upward? The answer is probably somewhere in between. Actions in the micro-, meso- and exo- systems impact the functioning of the macrosystem, and conversely, the large scale changes in the macrosystem diffuse downward. Marx stressed that individual action was futile in the face of historical movement (Breckmen, 1999). He did not leave much room for human action, he really only saw the movements of the macrosystem. Yet, as this paper has argued, to deny the potential of human action is to deny justice. And in order to inspire human actions, one must have a scheme or blueprint of social change. If we are witnessing the death of the Enlightenment, it is dying one student at a time. Only by mobilizing can the forces of resistance stymie this.

This website is one avenue of resistance. Individuals have the power to change their world, even if one microsystem at a time but they must be made conscious of it and of the levers of change. The macro-, exo-, meso- and microsytems of an individual can all be sites of contestation, where the individual can battle the oppressive social order, push for change and resuscitate the Enlightenment. According to Hedges, this is already happening (Hedges, 2013). Small victories by many people will begin to add up over time and force their way upwards toward the macrosystem. This paper has been mainly conjecture, anecdote and polemics, yet there is substantial evidence to support the points made and I encourage the reader to find it. This paper is meant to start a conversation, whether that is in a coffee shop, on Twitter or a classroom. Change without theory can and usually does degenerate into violence. This paper is meant to make people angry but more importantly to channel their anger toward action and justice.

References

Breckmen, W. (1999). Marx, the Young Hegelians, and the Origins of Radical Social Theory. Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P.A. (2006) The biological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., pp.793-828). Hoboken NJ: Wiley.

Evans, N., Forney, D. Guido, F., Patton, L. & Renn, K. (2010). Student development in college: Theory, research and practice. (2nd ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fowler, F (2009) Policy studies for educational leaders: An introduction. (3rd ed), New York, NY: Pearson.

Giroux, H. (2013) “Public intellectuals against the neoliberal university”. Published in Truthout. http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/19654-public-intellectuals-against-the-neoliberal-university

Giroux, H. (2011). On critical pedagogy. New York, NY: Continuum.

Gutek, G. (1995). A history of the western educational experience. (2nd ed). Illinois: Waveland Press.

Habermas, J. (1990). Modernity: An unfinished project. In Critical Theory: The essential readings, edited by David Ingram and Julia Simon-Ingram. New York, NY: Paragon House.

Hedges, C. (2013). “Our Invisible Revolution”. http://www.truthdig.com/repo/ite/our_invisible_revolution_20131028

Hill, D. (2012). “Fighting neoliberalism with education and activism”. Philosophers for Change

Janesick, V. (2007). Reflections on the violence of high-stakes testing and the soothing nature or critical pedagogy. In Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? Edited by Peter McLaren and Joe Kincheloe. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Jefferson, T. (2010). Notes on the state of Virginia. Introduction by Peter S. Onuf. New York, NY: Barnes and Noble Press.

Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Kiley, K. (2013) “Another Liberal Arts Critic”. Inside Higher Ed. http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/01/30/north-carolina-governor-joins-chorus-republicans-critical-liberal-arts

Kincheloe, J. (2007). Critical pedagogy in the twenty-first century; evolution for survival. In Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? Edited by Peter McLaren and Joe Kincheloe. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Leistyna, P. (2007). Neo-liberal nonsense. In Critical pedagogy: Where are we now? Edited by Peter McLaren and Joe Kincheloe. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Newfield, C. (2008). Unmaking the public university: The forty year assault on the middle class. Quincy, MA: Harvard University Press.

Peet, R. (2009). Unholy trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO. (2nd ed). New York, NY: Zed Books.

Zumeta, W. (2011). “What does it mean to be accountable? Dimensions and implications of higher education’s public accountability”. The Review of Higher Education, 35(1), 131- 148.

[Thank you Angelo for your support and this essay]

The writer is a doctoral student in higher education.

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change, philosophersforchange.org. Thanks for your support.

[Note: This piece may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the author. A different version of this piece appeared on Truthout.org]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Reblogged this on Guillotine mediocrity in all its forms!.

Your discussion of Bronfenbrenner brought to mind both Erik Erickson’s stages of psychosocial development and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and I couldn’t help but wonder if part of the problem with individuals today isn’t related to their basic needs going unmet so that all they can think about is how to fill that ‘hole’ that has followed them into adulthood. According to Erikson’s stages each stage is brought about because of some sort of ‘crisis’ — so that we have to master the crisis before proceeding on to the next stage. Conversely, in the case of Maslow’s hierarchy once a stage has been met we automatically proceed to the next one. And of course there is always Piaget and his four stages; the one I am interested in for this discussion is the concrete operational stage … it seems that many adults these days have never gone beyond that stage. Now, that’s not to say they are cognitively impaired per se, just that for whatever reason in the course of growing up they were never able to reach that final level.

I understand the Bronfenbrenner levels and can see the validity of using them in describing our current educational system, indeed, when you discuss how we seem to be teaching to a working (as in jobs) outcome that leads back to the lower levels in both Maslow’s hierarchy as well as Erikson’s psychosocial stages — our basic needs must be met before we can think critically about anything. And that follows to the current state of families that are without a roof over their heads, and even basic food needs being met. It seems to me that what is sorely missing in this country at this time is the upper stages of Maslow’s theory —

6. Aesthetic needs – appreciation and search for beauty, balance, form, etc.

7. Self-Actualization needs – realising personal potential, self-fulfillment, seeking personal growth and peak experiences.

8. Transcendence needs – helping others to achieve self-actualization.

Even those who are financially capable of reaching these levels don’t seem to be interested in doing that, and that’s not to say that it takes money to reach these levels, it doesn’t; rather, it takes a willingness to search outside oneself and that is what really seems to be missing in most citizens in this country today.

All in all, your treatise is enlightening, challenging, and well worth the read; thank you! 🙂

Pwr 2 the ENLIGHTENED peons!

GUILLOTINE MEDIOCRITY!